A USB-C YubiKey 5C security key plugged into my ThinkPad X1 Carbon

Every week I come across another headline about how someone got hacked and within moments many of their online accounts had become compromised. These aren't simple cases of bad actors using account credentials from large public data breaches and the unfortunate result of people using the same password across many websites.

These hacks, horror stories rather, are all the result of increasingly common attacks that gain access to a person's phone number by exploiting vulnerabilities in phone carriers. More advanced attacks prey on SS7, the old protocol underlying our cellular phone networks that lacks authentication. We more commonly hear about SIM card porting and SIM swapping attacks. In general, these attacks work by socially engineering your phone carrier to convince them you need a new SIM card as you lost your device or are upgrading it, or that you just want to switch carriers.

Today, many online accounts and services request your phone number to use as a form of account recovery as well as playing a role as a second factor in two-factor authentication via SMS text messages.1 These attacks aim to get access to your phone number so the attackers can reset whatever accounts are tied to the number.

Attackers especially want to reset important accounts like your email account. From there they are often able to reset other accounts that might not be linked to your phone number. It's a dangerous and all-too-quick sequence of events that can turn your life upside down in moments.

Increasingly, the end goal is to gain access to a cryptocurrency account like Coinbase or to steal a high-profile Instagram account handle; methods that can quickly be used to get money.

Just take a look at these headlines:

- Hackers Hit Twitter C.E.O. Jack Dorsey in a ‘SIM Swap.’ You’re at Risk, Too.

- The Most Expensive Lesson Of My Life: Details of SIM port hack

- Hackers Steal Over $300k From One of Blockchain’s Biggest VCs

- Wave of SIM swapping attacks hit US cryptocurrency users

- ‘I Lived a Nightmare:’ SIM Hijacking Victims Share Their Stories

- Everybody is getting tragically sim swapped and you will too

- The SIM Hijackers

- SIM Swapping Victims Who Lost Millions Are Pressuring Telcos to Protect Their Customers

- How to lose $8k worth of bitcoin in 15 minutes with Verizon and Coinbase

- SIM swap horror story: I've lost decades of data and Google won't lift a finger

- Hackers Are Holding High Profile Instagram Accounts Hostage

- FBI Issues Surprise New Cyber Attack Warning: Multi-Factor Auth Is Being Defeated

- Two-Factor Authentication Might Not Keep You Safe

A technology that can give you everything you want is a technology that can take away everything that you have.

—Dan Geer, Security analyst

I get freaked out every time I read one of those. As someone with a decent web presence, it feels like it’s only a matter of time before I become a victim of such an attack. While phone carriers have been working on making authentication better with efforts like Zenkey (née Project Verify) and the Mobile Authentication Taskforce, I think it’s best to take things into your own hands now, especially when technologies like Zenkey rely on mass adoption from third parties.

I've been a bit paranoid about security for a while now. It began as a curiosity for interesting new tools and services from installing PGP WDE in 2008 to encrypt my Mac (before FileVault 2 offered full-disk encryption) to exploring newer tools and services like VeraCrypt and Tarsnap.

SIM attacks like these, often the result of social engineering, are not the only thing to be worried about these days. Online phishing has become incredibly advanced, be it from official-looking texts asking for account info (smishing), malicious phone calls scams (vishing), email spoofing, brand impersonation, website spoofing and more. Take a look at this one:

Quick phishing demo. Would you fall for something like this? pic.twitter.com/phONMKHBle

— Mustafa Al-Bassam (@musalbas) September 9, 2018

Paranoia is not entirely unwarranted with the plethora of these attacks today. It was with this mix of curiosity and fear that I began using hardware security keys two years ago. In a nutshell, security keys are little devices (typically USB, NFC or Bluetooth) that compute cryptography keys and serve as a more secure second factor2 that only you can physically possess.

My assortment of Bluetooth, USB-A, USB-C, Lightning, NFC security keys

My evangelism of the benefits of these security keys amongst my friends has come up so often that I decided to write this beginner's guide (albeit rather detailed) to security keys—a topic generally left to very tech savvy people—to accomplish a few things:

- Encourage people to take a closer look at their personal online security.

- Explore what security keys are, understand the benefits and trade-offs, and see if security keys make sense for you.

Updates (Jan 2020)

There have been quite a few updates—really good updates—in the security key world since I published this article in October 2019. I have updated the respective sections throughout this article, but also wanted to note them in one place here:

Jun 2020

- Google has added WebAuthn support on iOS! This is huge news and something I've been waiting for. Now you can use USB, Lightning and NFC security keys in all Google login flows. Previously you could only use Bluetooth security keys via the Smart Lock app. The Yubico post has additional context.

Jan 2020

- Google has updated the Smart Lock app for iOS to utilize the built-in security key present on modern iPhones, the Secure Enclave. This new functionality is equivalent to what modern Android devices like the Pixel 3 and 4 can do with their integrated Titan security chips. Unfortunately, we're still waiting on Google to update their apps to fully support WebAuthn and allow logging in with USB, Lightning and NFC keys.

Dec 2019

- iOS 13.3 officially released and Safari gets FIDO2 WebAuthn support. This long-awaited update finally brings better WebAuthn support to iOS, starting with support in Safari for NFC, USB and Lightning security keys.

- Yubico Authenticator for iOS now supports NFC security keys.

Nov 2019

- iOS 13.3 Safari introduces FIDO2 security key support! Wow, I didn't expect to see this so soon. While still in beta and noted in the release notes, iOS 13.3 "supports NFC, USB, and Lightning FIDO2-compliant security keys in Safari" (and related Safari-powered view controllers that might be found inside apps). I can't understate how great this news is for iOS users. Lack of proper iOS support was the largest issue facing security key adoption and convenience.

- YubiKey Bio: Yubico announced they are working on a FIDO2 security key with an integrated fingerprint reader.

- Yubico Authenticator for iOS released. A lovely surprise with the release of Yubico Authenticator for iOS. This app lets you use your iPhone to access TOTP codes (not FIDO2) stored on your Lightning connector or NFC YubiKeys.

- OpenSSH to get U2F support. For those interested in easy native security key support with OpenSSH.

Security best practices

A few basics for improving your online security right now

Before I dive right into talking about security keys, I thought it would be best to discuss a few security best practices: low-hanging fruit that go a long way for improving your security online. There's a wealth of information on this topic across the web, so this is in no way meant to be an exhaustive list.

In addition, it really depends on a few things like what you are trying to protect, who might want it and where along the spectrum from convenience to security you would feel comfortable. Security folks would take this opportunity to talk about your personal threat model to help assess what level of security paranoia and defenses are warranted for you. That could probably be it's own article describing various routes to take and is fairly outside the scope of what I want to do with this article.

You can be on the supremely paranoid end of the spectrum but it would just make simple daily tasks like checking email and browsing the web a chore, and most likely just increase the likelihood of locking yourself out of your accounts.

Authentication is always a trade off between security and usability.

—Bruce Schneier, "Click here to kill yourself"

-

Use a password manager, religiously. Make sure the sync works or opt for a hosted cloud solution. Pick a very strong master password for the password manager and remember it. Don't use it for any other website or service. Backup the recovery key. Go through and change every online account password to something unique if it's your first time setting up the password manager.

I use and love 1Password and pay for the cloud account but there are plenty of alternatives out there including DashLane, LastPass (some people avoid it due to a history of security incidents and their acquisition by LogMeIn), Enpass and open source options like Bitwarden.

Set up Two-Factor Auth for your password manager if available. This is separate from 2FA for your accounts it stores and is just 2FA for the password manager itself. For example, a 2FA-enabled cloud-hosted 1Password account will ask you for your second factor when adding 1Password to any new device.

Regularly take advantage of advanced password manager functionality that evaluates your accounts to see if they have been involved in any data breaches (1P calls this Watchtower) as well as informs you when you reuse passwords.

-

Enable Two-Factor Authentication (2FA) wherever supported. Don’t enable SMS for your second factor if TOTP authenticator apps are an option.3 Enable 2FA using an authenticator app for all supported sites (we’ll get to security keys later).

You can use an authenticator app like Google Authenticator, Microsoft Authenticator, Yubico Authenticator4, FreeOTP (open sourced by Red Hat), AndOTP (open source and has encrypted backups), Duo Mobile and Authy5.

-

Backup account recovery codes if they exist, especially for important accounts and email providers like 1Password, Google and Apple accounts.

-

Remove your phone number as a recovery method for your email account. Ideally from all of your accounts, but we’ll get to that later.

-

Add a passphrase/PIN for your mobile phone carrier. This passphrase would be requested from the carrier to authorize any SIM port. Or at least that’s the idea. Unfortunately, phone carriers have been known to be socially engineered into not asking for it and attackers have been known to have insiders at telephone companies to bypass this.

-

Be a savvy web surfer. Much easier said than done, but lots of attack vectors are much closer to home than you might think. Keep your software up to date. Use an adblocker and/or DNS provider that can help keep you away from malware and phishing. (I have been testing out NextDNS.io and liking it so far. It's like a cloud-hosted Pi Hole if you don't want to bother setting that up yourself.) More popular options include Google Public DNS (while not an explicit privacy/adblocker type of DNS provider it does protect against several types of attacks), Cloudflare 1.1.1.1 and Quad9.

Consider using a VPN when you are on an untrusted connection, but know that a VPN merely changes who you are trusting but doesn't instantly make everything secure or private. Be skeptical of any browser extensions you install, links you click in emails, be careful when opening attachments and so on. Look for authentic website SSL certificates and correct domains when putting your credentials in a site. If your password manager can usually auto-fill in the details for a site but doesn't one day, it could be that you're not actually on the authentic site. So be sure to be suspicious if your password manager doesn't seem to be working as intended.

-

Revoke permissions for unused authenticated services. Go through your accounts like Google, Facebook and Twitter and revoke authenticated apps/integrations you no longer use or don't recognize that have any kind of access to your account. There’s probably way more than you recognize due to past single sign on uses.

-

Audit the authenticated devices linked to your Apple ID. Make sure you don’t have any old devices—maybe that you don’t use or no longer own—listed as devices in your account. And while we’re on the topic, make sure Find My iPhone is enabled so you can remotely disable a lost device in a pinch.

Getting more advanced

More tips for the increasingly paranoid

-

Secure your account with your domain name registrar. If you’re using email on a custom domain, ensure your domain name registrar is locked down with a strong password and two-factor auth using either an authenticator app or security keys. Remove any recovery phone number as well.

I’d recommend migrating your domains to something like Google Domains or AWS Route 53. Moving domains is easy. They offer strong 2FA solutions out of the box and I would trust them more than any other random registrar selling $5 domains.

This step is important because it’s another easy attack vector. Someone can socially engineer your registrar or mobile phone carrier (if linked), get access to your domain, change DNS MX records and then be able to receive password reset emails and take over other accounts.

-

Consider how and if you want to backup your authenticator codes. After you’ve got all your accounts set up with two-factor auth using an authenticator app, you need to think about what might happen if you lose your phone. With an app like Google Authenticator, you will lose the codes if you have to get a new phone and restore from an iCloud backup. There are convenient options like Authy and 1Password that let you easily backup these codes and access from any device. There's also AndOTP with it's encrypted backup capability.

1Password has a really lovely integration to also store these one-time password codes (and automatically paste them in when needed, depending on your app/extension/OS), but if you’re storing your second factor alongside your first, then you don’t really have two-factor authentication.

This solution is fine for most people, but this section is about being a bit more paranoid, so I would recommend not using the 1Password integration for your one-time password codes. Sure, you’re probably very screwed already in the unlikely event that someone gets access to your 1P database, but it’s even better if your most vital accounts require one more step by not having the OTP codes there.

The more extreme option is to manually keep track of the QR code or setup key provided when setting up 2FA for a TOTP authenticator on each account. Backing up these setup codes is a bit controversial and not recommended by the more hardcore security folks as it introduces another avenue by which you could be compromised if not securely stored. If you opt to backup your QR codes, you may want to store them outside of your password manager and in an encrypted manner. This could be on a service like Tarsnap, an encrypted Mac sparse bundle image or VeraCrypt volume. But now you have a new problem: how to securely store the passphrase or key for that service or volume.

-

Don’t set a recovery email for your email accounts. Depending on your level of paranoia, you may opt to remove any recovery email addresses linked to your email accounts. The logic here is that every linked recovery email is another potential attack vector that could be used to gain access to your primary email account.

If this sounds like a bit too much to you and you’re worried about just locking yourself out of your account, you should at the least ensure that the recovery email account has a strong password and two factor authentication enabled. And ideally this account is with different email provider, not added or logged in on any of your devices and is only used for recovery.

Switch your carrier to Google Fi

If you want another safety net

Even if you have done all you can to not link your online accounts to your phone number, there are always those services that just do not have two-factor authentication options beyond SMS. And that will always be a weak link in your security. You can do something like get a separate phone number that you only use for securing those accounts and don't use for anything else. You could also create a separate Google Voice number for that purpose; the benefit being that it's protected by your Google account's 2FA.

Or you can move switch your mobile phone carrier to Google Fi. I find this to be the simplest solution and have been using Fi for almost 4 years now. The security benefit here is that your phone number is now protected by your Google account's two-factor authentication, and is significantly less susceptible to social engineering attacks to gain account access.

I asked Google for more clarity on Fi security and was told the following. Basically, nothing is possible without access to the Google account already.

[...] we check for the authentication of their account and if a user contacts us with an unregistered email ID then we ask them to confirm their identity by sending secret codes to the email ID which they claim that have been registered with Google Fi.

Enable Google Advanced Protection

Consider Advanced Protection for your Google accounts

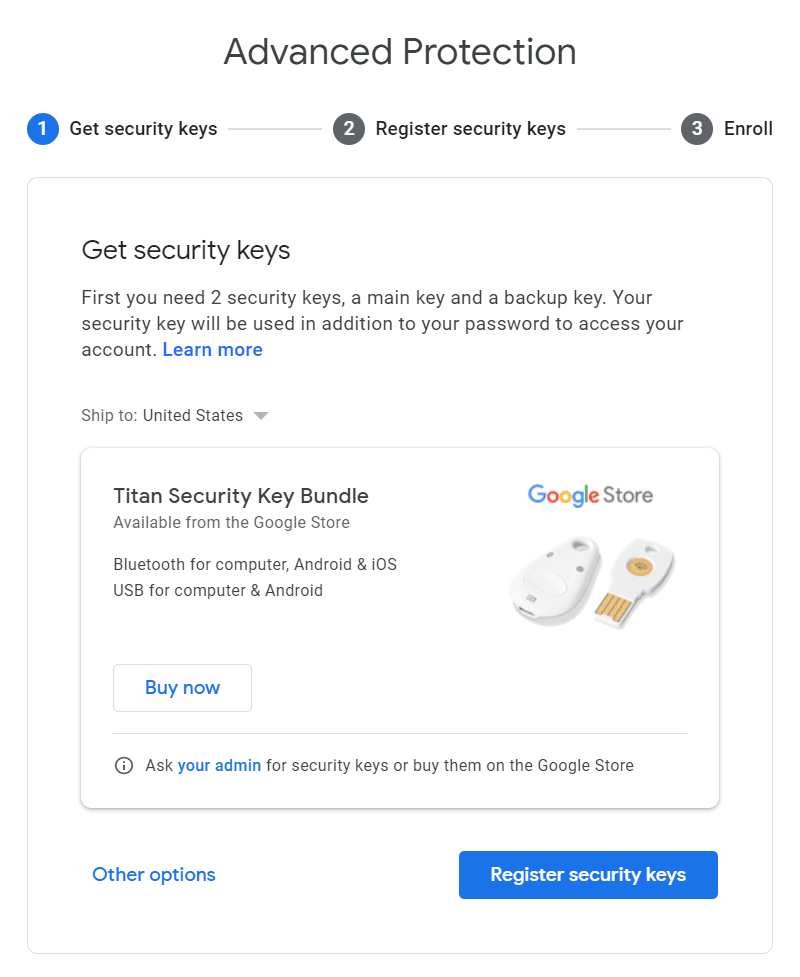

Google began offering something called Advanced Protection in late 2017. It offers enhanced security for those that might be at increased risk of targeted attacks. According to Google that includes journalists, celebrities, activists, business leaders, political campaign teams, firms dealing with cryptocurrencies and law firms. Fortunately, this functionality is available to anyone with a Google account and it brings some significant changes.

Targeted attacks could be low volume, carefully crafted, phishing attacks, often personalized to individuals, and can be hard to distinguish from legitimate activity. This makes targeted attacks the hardest to protect against. The Advanced Protection Program is specifically designed to thwart targeted online attacks on Google accounts.

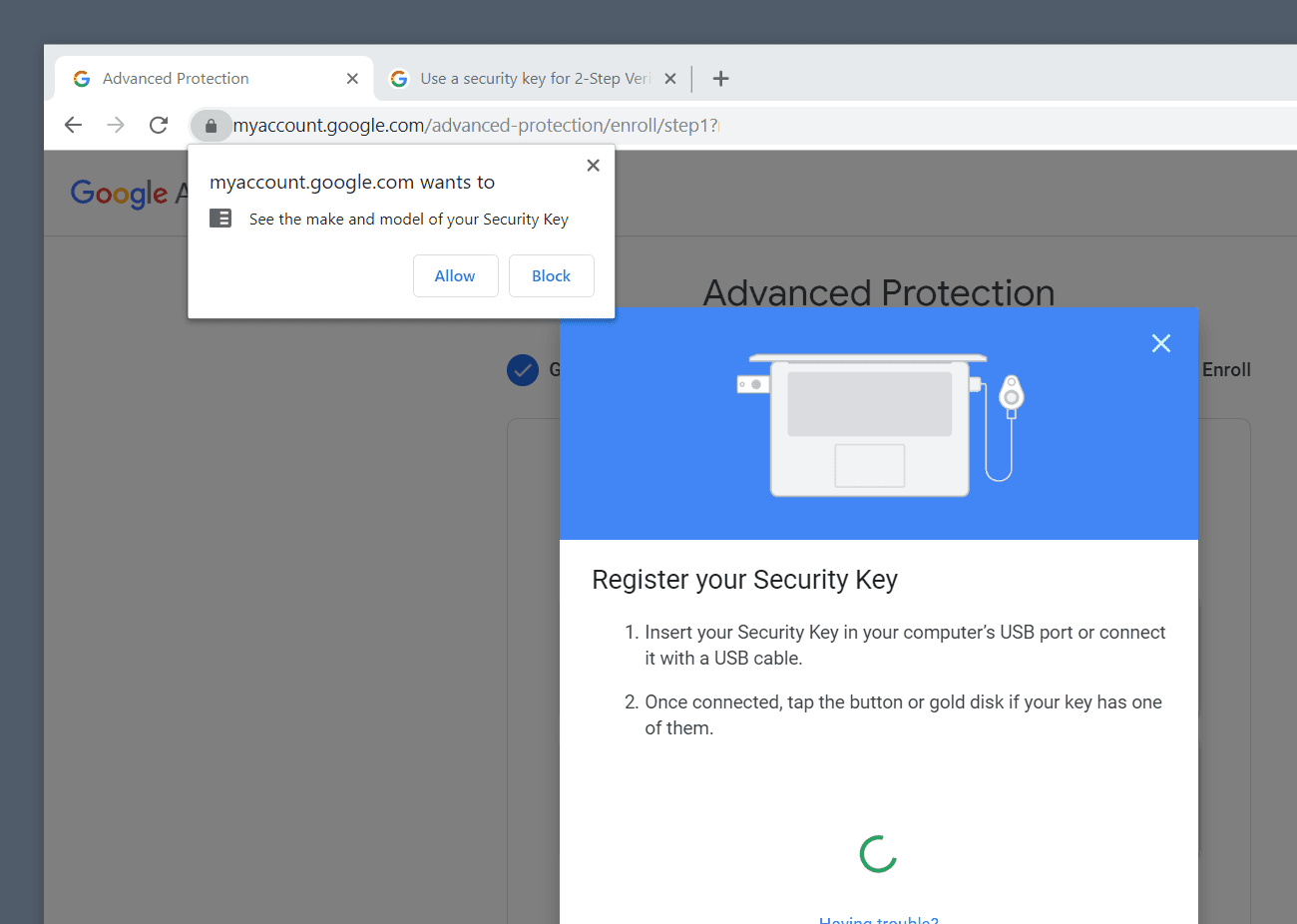

First, Advanced Protection requires that you use security keys. It won't let you enable it until you pair two security keys to ensure you have a backup key. The main benefit here being that security keys prevent phishing. Google accounts with AP enabled also bring stringent changes like:

- Very strict account access rules for your emails and Google Drive files. This means you won't be able to use your Google account outside of native Google apps, except for a select list of trusted third-party applications like Apple Mail, Apple Calendar, Apple Contacts and Mozilla Thunderbird.

- App passwords are no longer supported

- Exhaustive Gmail scans to catch phishing messages and attachments containing malware.

- No recovery code. That’s right. If you don't have access to your password and one of your security keys, there is no way back in. You must go through the recovery process, which is much more rigorous and includes various delays on purpose. They may ask recovery questions like what month and year you first opened the Google account.

- Enhanced web browsing safety when signed into Google Chrome. Google will alert you if it detects you downloading a file it thinks is unsafe according to its Safe Browsing policies.

- And finally, I feel like Advanced Protection is more suspicious of activities and will aggressively prevent logging in if it thinks something is astray. I recall trying to test it out and logged in and out of my account on various devices and different IPs on VPNs and it was quick to prevent access.

Google Advanced Protection may be overkill for some people but it's a good segue into security keys and how they can help enhance your online security.

Further reading

As I mentioned earlier, there's a wealth of security-related information, guides and research available online. I just wanted to provide a few starting points in this section. However, one area that deserves a mention is considering so-called privacy-first applications, services and providers. They are typically open source programs or services from companies that are very transparent about every facet of their practices related to user privacy, data handling and dealing with authorities.

You might have heard of some of the common privacy-first solutions: DuckDuckGo instead of Google, ProtonMail instead of Gmail, Firefox/Tor Browser instead of Chrome, various Linux distros instead of Windows 10 (at least run W10Privacy), Signal instead of SMS/WhatsApp and so on. PrivacyTools.io is an amazing resource covering a slew of privacy-first applications, services/providers, tools and more. I particularly enjoyed the page about the fourteen eyes, key disclosure laws and warrant canaries.

What are security keys?

The small hardware devices to enhance your online security.

Security keys are inexpensive, little hardware devices that use public-key cryptography to securely authenticate the website to the key. Maybe you've seen them around; these security tokens tend to look similar to regular USB memory sticks. Compared to using an authenticator app (also known as a TOTP code generator) as a second factor for 2FA, security keys (also called external or roaming authenticators) are a preferred and more secure option.

USB-C security key plugged into a Pixel 3 Android phone.

When you go to log into a website where you have registered a security key as your second factor, you are first prompted for your username and password and then for the key. Usually this means plugging in and touching a special touch sensitive area of the key (for USB keys), but could also mean bringing the key closer (NFC) or pairing and pressing a button on the key in the case of Bluetooth security keys.

Okay, sounds easy enough.. but a bit more of a hassle to keep another device handy, right? So what’s so great about these security keys?

It’s no coincidence that Google requires hardware security keys as the second factor method for Google accounts with Advanced Protection enabled. Google themselves pushed for their employees to use security keys and they saw that it entirely neutralized phishing attacks on all of their 85,000+ employees.

Compared to TOTP authenticators, the key benefit of using a security key is that they are immune to phishing attacks.6 This is partially due to the fact that the origin/domain of the website is taken into account when you register your key. If you fall for a credential phishing email and went to log into a look-alike fake website, verification would fail, even if you thought the website was real.

YubiKey 5C Nano plugged into my ThinkPad X1 Carbon

Security key history

FIDO, U2F, CTAP, WebAuthn.. where did it come from?

But first I wanted to briefly dive into the history of security keys over the last few years. For the purpose of this article, I want to refer to these hardware authenticators and security keys as just security keys. You may have seen them referred to as FIDO U2F, CTAP, FIDO2 and WebAuthn. It’s all very confusing and even the newer overarching and correct term (FIDO2) doesn’t quite roll off the tongue.

You may be thinking, wait a minute, I used hardware tokens years before this. And you’re not wrong. Code generating hardware tokens like RSA SecurID have been around since the early 2000s. They would continually display newly generated codes on their LCD display: codes that would often be appended to a password when logging in.

Then there were USB security keys in 2007 that would identify themselves to the computer as standard USB HID keyboard input devices and as such, not require any special drivers. When pressed, they would input a one-time password string comprised of things like counters, timers and random values. The one-time password would then be verified by the server based on a shared state (like the usage counter and device id) between the server and key.

While those keys sound a lot like the keys we have today, their implementation is quite a bit different and they are still susceptible to phishing and man-in-the-middle attacks.

Fast-forward to 2012. Google and Yubico collaborated on a hardware security key based on public-key cryptography. This eventually became known as U2F (Universal 2nd Factor) and became part of the FIDO Alliance (Fast IDentity Online), an organization initially founded by PayPal, Lenovo and other companies to work on a passwordless authentication protocol.

In 2014, Google officially shipped FIDO U2F support in their Chrome browser. The next few years brought better security key hardware, increased support from large, mainstream websites like GitHub, Facebook and Dropbox, as well as increased support from browser vendors.

Now, in 2019, we have the FIDO2 project. It recognizes the growing need to enable easy and secure multi-factor authentication experiences across both desktop and mobile devices to further the FIDO Alliance's goal while making strong authentication more accessible. FIDO2 consists of two distinct parts: a client API called WebAuthn (an official W3C standard created in collaboration with the FIDO Alliance) and an API for hardware authenticators.

FIDO2 = WebAuthn + CTAP

The first part, WebAuthn (short for Web Authentication), is essentially the client/browser JavaScript API that allows websites to create and use credentials based on public keys, which may come from hardware authenticators. It’s huge news that this is now a W3C standard so that every browser manufacturer can begin developing and supporting it. WebAuthn is the core link between the website server—frequently referred to as the Relying Party—and the browser.

The second part helps define the link between the browser and the external authenticator device. This protocol is called the Client to Authenticator Protocol, or just CTAP.7 This aids in all the particulars of how various hardware authenticators communicate with the browser, such as via USB, Bluetooth Low Energy and NFC.

What is passwordless?

What is this passwordless thing all about?

One thing I keep hearing about with respect to authentication these days is passwordless auth. Honestly, it just seems like a buzzword.. so what exactly is passwordless? I'll briefly describe the premise here and why it's not the focus of this article.

One of the primary goals of the FIDO Alliance at its inception was to provide "open and free authentication standards to help reduce the world's reliance on passwords." So far in this article when talking about FIDO1 I have only mentioned Universal 2nd Factor (U2F), which eponymously refers to enhancing two-factor authentication by using hardware security keys as a second factor.

FIDO U2F became well-known, in no small part to strong support from Google and subsequent integration into the Chrome browser. And well, U2F is comparatively easy to understand for people already familiar with two-factor auth... you just use a key you plug in as your second factor. Easy enough.

FIDO1 also contained a spec for something called UAF, Universal Authentication Framework. Its original goal was to provide a passwordless authentication solution employing biometrics. Similar to U2F, UAF utilizes public-key cryptography to authenticate with each service.

The difference is that UAF does not require any password. The browser asks the user to complete their previously registered authentication gesture, such as tapping their finger on a fingerprint reader or typing in a PIN.8 As such, it's called passwordless since no password is actually sent across the network. The authentication is done with the standard challenge-response auth as part of public-key cryptography.

Okay, so what about FIDO2? FIDO2 brings WebAuthn, which essentially merges the capabilities of U2F and UAF into one API that can be accessed by any supported browser or OS. People utilizing FIDO2 for two-factor auth with a security key as their second factor now have the ability to use a broader set of authenticators, such as internal platform authenticators like fingerprint readers and facial biometrics built into their devices. And finally, FIDO2 provides various passwordless authentication formats into the same system: passwordless single-factor or multi-factor.9

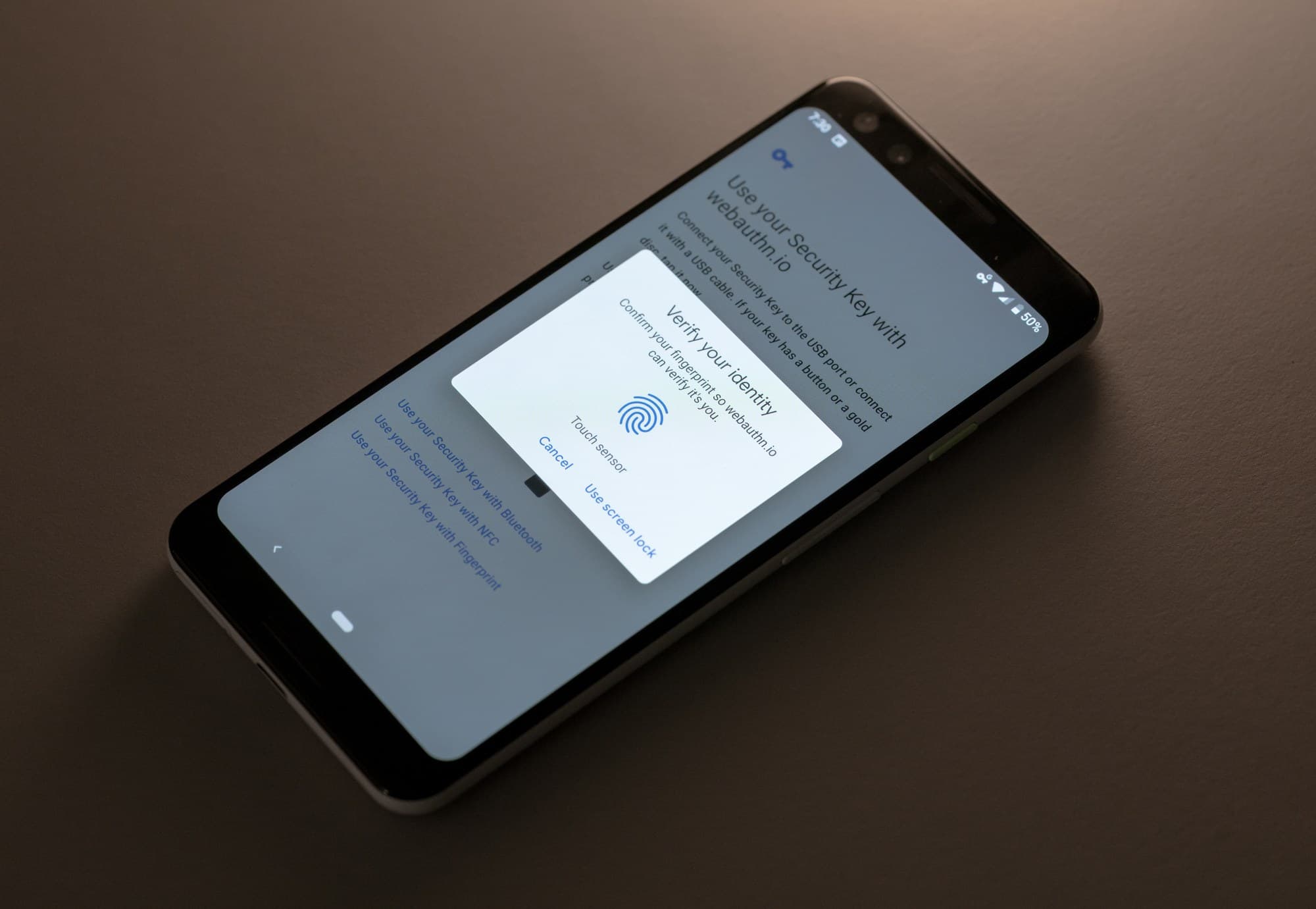

Android supports built-in platform authenticators like fingerprint readers. Here's an example flow.

All of this work is done to make passwords obsolete...why?

Passwords have several notable issues. Strong passwords are hard to memorize, they take time to type, many people still use the same password for all of their accounts and it's easier to be phished with just a password. And of course, should anyone get access your password, they can just use it right away to log in.

But these seem like relatively solved issues today, right? We have robust password managers and we have two-factor authentication. The thinking behind passwordless is that those are just workarounds to an ancient authentication system that should be re-imagined with the latest technology we have at our disposal today.

We already have a taste of what FIDO2 brings today with enhanced authenticator support: you can use Touch ID on your MacBook Pro in Chrome, the fingerprint reader on your Windows 10 device via Windows Hello or even use the Pixel 3 Android phone itself as an authenticator, storing credentials inside its Titan M security chip and more. And you can imagine that in the future smart watches could begin to function as authenticators too: Apple already lets you use your Apple Watch as a proximity-based authenticator to unlock your Mac.

TouchID working with WebAuthn in Google Chrome

The passwordless vision is compelling but feels quite a few steps away. First, barely any websites even support passwordless authentication flows.10 Second, passwordless functionality requires storing data like display name and relying party name on the security key itself—something that doesn't happen when simply using your security key as a second factor. This is called a resident key credential and this data takes up space. Modern YubiKeys only have storage room for 25 resident keys11 for use with such passwordless auth. Sure that might be a moot point if we all end up using internal platform biometric authenticators12 for everything, but biometrics aren't a flawless13 solution:

Biometrics are easy, convenient, and when used properly, very secure; they're just not a panacea. Understanding how they work and fail is critical to understanding when they improve security and when they don't.

—Bruce Schneier, Security expert

The very compelling counter-argument is that, well, people just know how to use passwords and not everyone understands (or cares!) about security. We've finally made some headway on getting people to use two-factor authentication.

It's for those reasons that I would like to focus on the here and now: learning about the benefits of hardware security keys and how you can begin using them today with many services you already use.

Security keys vs. auth apps

Are security keys really any better than TOTP code generator apps for 2FA?

Before I go into detail about how security keys work and their benefits, it might make sense to talk a bit about the issues with using authenticator apps for two-factor auth.

TOTP risks

Why authenticator apps aren't perfect

Even though they are a vastly preferred second factor compared to SMS, authentication with TOTP (Time-based One-Time Password) has some risks and inconveniences compared to security keys employing public-key cryptography.

-

Lack of phishing prevention. A huge issue with TOTP is that there is no inherent replay attack protection. You could still fall victim to a fake website (or real one being proxied via man-in-the-middle like with Evilginx 2 and Modlishka) looking exactly like a website you visit and supply your password and TOTP codes to them. The attacker or bot can then log into the real website as you and still be within the TOTP time limit.

-

TOTP employs a shared secret. With TOTP, the website has a secret key it provides to you. This is the key your authenticator app uses for initial setup. The TOTP authenticator then generates a hash with the secret key and the current time. The website does the same thing on its end, using the same secret key it has, and compares the two.

The issue is that the user and the relying party website share and store the same key. Unless the website followed the security recommendation in the TOTP spec to encrypt the secret key and only decrypt when in use to limit exposure in memory, it’s possible an attacker could generate TOTP codes for any account.14

-

Manual code entry. A significant and frequent annoyance with TOTP codes is that you have to manually type in the code each time: not to mention open your phone, then open the authenticator app. There are, however, methods of simplifying this with desktop authenticator apps, especially with password managers like 1Password automatically copying and pasting it in for you, but you don't really want to have your password manager also store OTPs.

-

Backing up TOTP authenticators is a hassle. Lose your phone where you had the only setup of Google Authenticator? You will need to proceed to account recovery for every account you had in there, which may go through an SMS (hopefully you’ve disabled this already!) or email reset flow. That’s annoying.

There are some modern solutions to backing up and syncing your authenticator app in the cloud like Authy, using the OTP integration in 1Password or managing andOTP encrypted backups. But that’s up to you to decide if those routes are for you as they have some downsides. You can also decide if you prefer to backup the TOTP setup secret key or QR code, but it would need to be stored securely as to not introduce another attack vector.

But I digress, my point here is that backing up your authenticator is yet another thing to think and worry about with TOTP.

Security key benefits

No shared secret, phishing prevention and much more

On the other hand, security keys work in a very different manner and avoid many of the issues inherent with TOTP authenticators. Security keys are based on public key cryptography, meaning there is no shared secret between the user and the website. The benefit here is that even if a website was breached and an attacker gained access to a user's public key, they would not be able to do anything with it.

My 90mm macro lens was a great investment and was used thoroughly in this post.

In addition, security keys are designed to make it impossible to get the private key out of the security key itself as cryptographic functions are computed locally on the device and never exposed to the computer.

-

Bulletproof phishing protection. The largest benefit of security keys is that they entirely thwart phishing attempts unlike TOTP authenticators. The exact domain name of the website is taken into account when the security key is registered. Even if the user willingly tried to log into a fake phishing site, the security key authentication would not work as the domain would differ. There's also support for token binding which furthers this protection, though I'm not sure it is widely supported yet.

-

Security keys prevent replay attacks. Security keys are designed to never expose private keys outside of the hardware. However, should they somehow be cloned, they contain a signature counter. The WebAuthn spec says the security key should provide an incremental counter to the relying party on each successful authentication. Should the value not match the last known value, the authentication should fail. I say should because this is not a strict requirement for WebAuthn and it doesn't appear to be common yet.

In addition, security keys and the relying parties utilize a challenge-response authentication flow to ensure single use and further prevent replay attacks.

-

Built-in user presence required. One of the core features of security keys from the beginning has been that they require user presence before the key can do any cryptographic operations. All security keys require you to prove your presence by physically touching a capacitive touch sensor (or button for Bluetooth keys). This prevents remote takeovers as the user has to prove their physical presence to the device. Newer FIDO2 keys support user verification where you need to provide a PIN or a biometric gesture like a fingerprint tap (like with the upcoming YubiKey Bio with integrated fingerprint reader) if configured as such.

-

No typing in codes. And after you tap the key, that’s it. There’s no more work to do, you’re already logged in. However, this assumes you already have the key plugged in your machine and don’t have to fish it out of your pocket or bag.

-

Easy to backup. Backing up a security key is easy—just buy spare security keys and register them on each service!

-

Privacy as default. And finally, since security keys generate unique public/private key pairs for each website, it is impossible for anyone to know what sites are registered to your security key. Even if your key is stolen, there is no way to know what websites it is used with, or any associated data.15

Types of security keys

How many keys do you need? How much do they cost?

That’s a long way of saying that security keys are a terrific option to increase your online security. Now we can go into some more actionable info: basics about the security keys themselves, how many you need and what kind.

You’ll need to buy some security keys of course before you can get started. FIDO2 and WebAuthn paint a vivid picture of the future of authentication from supporting more types of authenticators—from numerous internal biometric sensors to more types of mobile devices—to supporting passwordless authentication flows.

As I mentioned earlier, external security key authenticators are the easiest to incorporate into your daily life today compared to passwordless auth. It won't be perfect though: there are still some inconveniences and support issues associated with using security keys for your two-factor auth that I’ll dive into later.

How many do I need?

Yes, you need to purchase your security keys and they are not free. This is quite different than past solutions like SMS and TOTP authenticator apps. But it’s a small price to pay for enhanced security and phishing prevention. Security keys come in many varieties (USB-A, USB-C, NFC, Bluetooth LE and most recently, Lightning connector) to interface with computers and mobile devices.

There are benefits to using only one security key, but having multiple keys to rely on as your second factor is ideal.

-

Purchase two or more keys if you want to rely entirely on security keys—and fully disable SMS and TOTP authenticator apps where possible—you will want at least 2 keys so that you can have a backup key. That being said, most services let you program many keys so there is not much harm in having a few more (unless they are too easily misplaced or haphazardly stored and fall into the wrong hands). You may also find it handy to have small "nano" keys that always stay plugged in your computer.

You will need at least two keys if you want to consider enabling Google Advanced Protection on your account.

-

Purchase one key if you want to test it out. There is still a strong benefit to just using one security key as a second factor in addition to a TOTP authenticator app as your backup. By relying on your security key to authenticate as much as possible, you’ll still receive the strong phishing protection that comes with security key usage.

YubiKeys are pretty durable. I've had this one on my keychain for a year and a half now. I have heard people say the USB-C version is less durable than the USB-A version but I haven't had any issues myself.

How much do they cost?

Depending on feature set and durability, security keys range in price from around $10 all the way to $100+.

-

Entry-level: At the entry-level, we have security keys that cost something like $12 HyperFIDO Mini, $20 for a Yubico Security Key and the open source SoloKey.

These cheaper keys tend to be strictly for authentication via one protocol only and won't support additional protocols and software customization that pricier keys have—which is totally fine. Some keys in this price range may only support FIDO U2F and not the latest FIDO2 spec (aside from the model by Yubico). This means you can't use them for new WebAuthn passwordless functionality if that matters to you.

-

Mid to top tier: The main players in this space are Google (with the Google Titan Security Key bundle as well as the just-released USB-C version that is similar to the Yubico 5C) and Yubico with their latest YubiKey 5 series offerings like the flagship $70 YubiKey 5Ci featuring dual USB-C and Apple Lightning connectors.

At this level you start to see more durable keys with better build quality, as well as support for many applications in addition to FIDO U2F and FIDO216, such as Yubico OTP, Smart Card, OATH and OpenPGP. But most of these probably mean very little to you unless you're a developer.

Left: YubiKey 5Ci (Lightning connector) with iPhone 11 Pro Right: Titan Security Key bundle

- Advanced & specialized: At the high-end there are devices that do much more than just U2F authentication and have robust, integrated password managers and cryptocurrency wallets. Trezor and Ledger both offer models in the $50 to $120+ range.

I should also mention that there is a slowly growing category of devices not listed above that will become more important in the future as passwordless auth expands: external FIDO2 biometric authenticators. These devices are full-fledged FIDO2 security keys but also contain a biometric sensor like a fingerprint reader.

The fingerprint reader comes in handy for local user verification (instead of a PIN) for multi-factor passwordless auth. For example, like this Feitian BioPass authenticator. But I can't vouch for that brand and don't know if it requires special fingerprint drivers like similar models do. But I digress, this doesn't matter right now, especially as I'm focusing on two-factor auth security key uses.

Update (Nov 2019): Yubico has since announced that they are working on YubiKey Bio, a security key featuring an integrated fingerprint reader that has no battery and requires no additional drivers or software to function. Unfortunately, it appears that this first biometric security key from Yubico is only USB-A.

Compatibility issues

A look at what supports WebAuthn

There are two pieces to successfully adopting security keys: support for FIDO U2F or FIDO2 WebAuthn from websites you use and the same support on the browsers and devices you wish to use to access those websites or apps.

Both have been a bit confusing for various reasons. Take website support of FIDO U2F or FIDO2 WebAuthn for example. A website may support one of those and let you register your security key, but it's up to the site's specific two-factor auth implementation to determine whether you will be allowed to register multiple security keys and/or use security keys as your only type of second factor. One reason is that that website's accompanying mobile app may not support security key login and they don't want to have to explain this trade-off to users.

Spotty browser support has been a big issue over the years. This really comes down to the devices you use, as well as their current state of support for security keys. While security keys come in many flavors spanning USB-A, USB-C, NFC, BLE and Apple Lightning connector, just because the port fits into your device doesn't mean it will work everywhere on your device.

Support for security keys is by no means ubiquitous across devices, operating systems and browsers and websites. Things have gotten much, much better over the years and really, the only real rough patch lies with iOS. I'll dive into a brief description of the current support landscape right now, but one way to keep up to date on WebAuthn support status is by checking CanIUse.

Windows - Great support

You can use any USB security key on Windows 10 with Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, Brave and Microsoft Edge.

Windows 10's Hello authentication system also supports FIDO2 security keys and currently the Edge browser has WebAuthn integration to access additional Hello-supported authentication methods such as PIN and biometric readers.

Linux - Great support

USB security keys should be fully supported by any modern Linux distro as well as a browser like Chrome, Chromium and Firefox. However, certain distros may require you to manually tinker with the udev device management subsystem to enable browsers to interact with security keys.

ChromeOS - Great support

Supports USB security keys. Certain Chromebooks also feature their own integrated Google H1 CR50 security chip so you don't even need an external security key, but I believe they only operate as a FIDO U2F+CTAP1 key.

macOS - Great support

While security keys are fully supported on Chrome and Firefox for macOS, Safari has lagged behind and not had support for a while. Fortunately, Safari 13 shipping with macOS 10.15 Catalina brings FIDO U2F and FIDO2 WebAuthn support.

If you're not on Catalina yet, you're able to put it to use with the Safari Technology Preview now, but it does appear to entirely lack basic UI to show when a site is requesting key access. Chrome also supports biometrics with WebAuthn, letting you access TouchID on TouchID-sporting hardware like the MacBook Pro and MacBook Air. No FaceID support and no word if that will happen.

Android - Great support

Android support for security keys is in a great state, and that's no surprise with Google's push for U2F, and now WebAuthn, since the beginning. Chrome and Firefox enjoy full FIDO2 support and this means you can easily opt to use USB, Bluetooth and NFC security keys, along with any integrated biometrics such as your device's fingerprint reader. (However, Brave browser and Firefox Focus did not appear to have functioning security key support at the time I wrote this.)

In addition, the Android OS itself is FIDO2 certified. The OS-level integration means that browsers and other apps only need to make an API call to trigger Android's robust auth flow that handles everything.

Using a USB-C security key on a Pixel 3

iOS - Great support (Updated 2024)

Update 2024: Things have come a long way and you're no longer at a disadvantage using a security key with iOS.

The state of security key support on iOS used to be utterly horrible. The native Safari browser didn't support any kind of web authentication. The only option was to use a special Lightning connector security key and a different browser that had security key support baked in (Brave for iOS).

The only other way to work around it was with custom solutions employing Bluetooth security keys. Google lets people use security keys on iOS by redirecting to a separate app called Google Smart Lock that can pair with Bluetooth security keys—an annoying, one-off and clunky solution only for Google services.

Fortunately, things have changed for the better. They're still not great, but they're on the right track. As of December 2019, Apple released iOS 13.3 which brought Safari support for WebAuthn using USB, NFC and Lightning connector FIDO2 security keys.

Even though Safari supports WebAuthn now, this does not mean that everything on iOS will. Many apps are in need of software updates to let you use security keys. Since iOS had no security key support for ages, it's likely that many apps just incorrectly assume that iOS as a whole can't interface with security keys and won't even let iOS users provide their security key. Gmail is one such example: both the iOS app and website in Safari won't let you use a USB, NFC or Lightning connector security key yet. Update (Jun 2020): Google now supports USB, NFC and Lightning connector security keys for WebAuthn on iOS!

This is also the current state of support for the aforementioned YubiKey 5Ci Lightning connector security key. It only works with a small set of apps and browsers like 1Password, LastPass, Safari and Brave browser.

A note about NFC keys Don't modern iPhones have NFC? Can't we use that along with NFC security keys for authentication?

Fortunately, the short answer is yes! Unfortunately, this was literally only possible until late in 2019 with iOS 13 bringing full read/write NFC support to devices like the iPhone 7 and newer. And then it wasn't available to consumers until iOS 13.3 brought NFC key support into Safari in December 2019.

In the past iOS provided read-only NFC access on iPhones. You might have seen some examples of NFC security key authentication on iPhones in the past (in case you've seen the LastPass integration advertised). Those solutions have also been proprietary (sound familiar?) and required custom integration with the YubiKey Mobile SDK as they did not use FIDO U2F or FIDO2/WebAuthn, but instead used the proprietary YubiKey OTP. That was the only option at the time because FIDO U2F and FIDO2 require NFC read-write access to function, which iOS did not allow at the time.

Safari does now support the use of NFC keys and it's a great and easy experience. App and other browser developers (looking at you Chrome!) will still need to manually add support for this functionality. Yubico Authenticator for iOS was recently updated to support NFC keys so you can also use the key for TOTP code generation purposes in addition to WebAuthn. However, NFC is not a perfect solution with mixed support: current iPads and older iPhones don't have the necessary NFC hardware.

Update (Jun 2020): Google now supports NFC security keys for WebAuthn on iOS, so if you're primarily using a security key for Google products and services, now is a great time to consider an NFC key.

Left: iPhone 11 Pro + YubiKey 5Ci Lightning connector security key Right: Using the 5Ci withBrave browser for iOS

Buying your keys

NFC, BLE, USB-C, oh my! What to choose?

Hopefully you now have enough context about the compatibility landscape to help you make an informed decision about what security keys to purchase given your mobile and desktop computing needs today.

If every type of security key was well-supported everywhere, you would probably just want a USB-C key for your computer and NFC key for your mobile devices. Holding your NFC key up against your phone for a moment is such an easy task compared to plugging anything into the USB-C port—dramatically easier than using a Bluetooth key that constantly needs to be charged, uses an archaic Micro-USB port and has to be paired.

But that would be too easy. Unfortunately, we're stuck with a not-so-great matrix of varied security key support across devices, operating systems and browsers. Below I've put together some personal security key recommendations depending on what mobile device you use. I focused on mobile devices as the differentiator as desktop support is already fantastic for any USB key.

New users

For those that want to test the waters first

If you're not sure if you want to fully commit to security keys right now but want to give it a try, I'd recommend starting off with an affordable, no-frills USB-A key like the Security Key by Yubico. It's perfect for letting you try out web authentication flows on your desktop computer easily. Even having one key would still provide benefit of protecting you from phishing attempts while serving as just an extra second factor authentication method alongside your current TOTP/authenticator app.

Just note that this model cannot be used with desktop and mobile Yubico Authenticator apps to store TOTP secrets and function as an authenticator app for services that don't support security keys yet. Those are reserved for higher-end "YubiKey" series keys from Yubico.

Recommendation for iOS users

Lightning, NFC, USB keys & limitations

If you use iOS today, your best bet it to use either an NFC key or a Lightning connector key. Unfortunately, while Yubico has announced that they will release an NFC key that is also USB-C in Q1 2020, it's not out yet. Until then, I would recommend the YubiKey 5Ci that is both Lightning connector and USB-C.

A dual USB-C and Lightning connector YubiKey will also be handy if you need to use this on an iPad as current iPads do not have any NFC hardware. An NFC key may prove to be more convenient if you only plan to use it with your iPhone.

-

YubiKey 5Ci: Dual Lightning connector and USB-C FIDO2 security key. — Amazon · Yubico

-

YubiKey 5 NFC: NFC/USB-A key. FIDO2 & multi-protocol — Amazon · Yubico

-

YubiKey 5C: USB-C FIDO2 & multi-protocol security key — Amazon · Yubico

For Google users

Of course, it's not that easy. If you use Google services, you will need a Bluetooth key17 as they have not yet updated to take advantage of Safari's WebAuthn support nor implement their own into Chrome for iOS. And then your best bet is to also get a USB-C key for desktop use.

Unfortunately, no great Bluetooth keys exist. They all seem mediocre19 in terms of design, durability, usability and lacking FIDO2 support. And then there's the fact that many of these keys, like ones by Feitian and Thetis, are made in China. Paranoid security folks avoid them due to concerns around untrustworthy firmware.

The Bluetooth key I'm linking to here is Google's Bluetooth Titan Security Key. These keys are essentially rebranded Feitian keys loaded with Google's own firmware. These keys seem to be only FIDO U2F keys, not the latest FIDO2, so there is no WebAuthn passwordless support.

Up until recently, the Titan Key was only sold in a bundle, but Google recently began selling them separately, along when they announced their new USB-C key. Google's new USB-C Titan key is created by Yubico but is neutered and lacks the flagship Yubico features I would have expected: support for multiple protocols (mainly to be able to use Yubico Authenticator) and full FIDO2 support. As such, I recommend the YubiKey 5C20 instead.

If these options are limiting for you and the services you wish to use won't work with a Bluetooth key on iOS (at this time that's most things not Google), there is one fallback: adding an authenticator app as another second factor to use for these scenarios.

Update (Jun 2020): Google now supports WebAuthn for iOS with USB, NFC and Lightning connector security keys! This is huge news and means you no longer have to rely on sub-par Bluetooth security keys. As such I am removing my recommendation for Bluetooth security keys.

That being said, Chrome for iOS does not yet support WebAuthn but Google has been making great progress lately between this update and their recent Google Smart Lock update, so a Chrome for iOS update can't be too far away.

There's no way around it: Bluetooth security keys are annoying.

Recommendation for Android users

Use whatever you like, Android is the best.

If you use Android, you can basically do whatever you want: support for all sorts of keys across Android is great. Personally, I would just recommend going for multiple USB-C keys (assuming your desktop computer is also USB-C).

I tend to prefer the smaller form factor keys over the slight convenience benefit of a larger NFC key, but that really comes down to personal preference. When the NFC version of the YubiKey 5C comes out, I would recommend that over the USB-A version shown below.

About nano-sized keys

Tiny keys for frequent use

Nano-sized security keys are made to be remarkably low-profile and meant to remain in a USB port. They're so small that they're even a bit annoying to remove—and you're likely to lose them if you do.

They're intended for keeping in computers, or even servers, where security key functionality will be used frequently and ease-of-access to touch the key is important. I find having one plugged into the USB port on my desktop's monitor to be very handy: only a short distance to tap it when I need to login. But this will especially be handy for those doing more with their security keys than just two-factor auth, like using it for PGP and SSH keys.

It's up to you to decide if you would feel comfortable using a nano key in a laptop you travel with where there is a risk of the two being stolen together, compared to a stationary desktop computer.

Nano-sized keys live in the USB port of your computer, ideal for cases where they will be used frequently.

An ode to Yubico

I really love Yubico security keys. It's no surprise that one of the original companies pushing for strong authentication online knows the importance of high quality, durable hardware. I’ve never had any issues with Yubico build quality and their higher-end YubiKey series supports a robust feature set that's customizable with software. It costs a premium but you can trust it and they are known to do recalls if they suspect there are any issues that could affect security (they replaced one of my older 4C keys).

If I had to nitpick, their software (YubiKey Personalization Tool, YubiKey Manager, Yubico Authenticator) isn't simple or well-designed.

There is, however, one significant criticism about Yubico keys from security folks in the industry. It's that Yubico's keys are closed source, preventing developer community-sourced verification of secure code along with the ability to update and modify the device however the owner wishes. For customers that fall in that camp, there are open source options like SoloKeys.

Hopefully that all made some sense! If you're still not sure what you need, it might be worth checking out this quiz from Yubico to help you find the right security key for your needs.

Registering your keys

Using security keys for two-factor auth

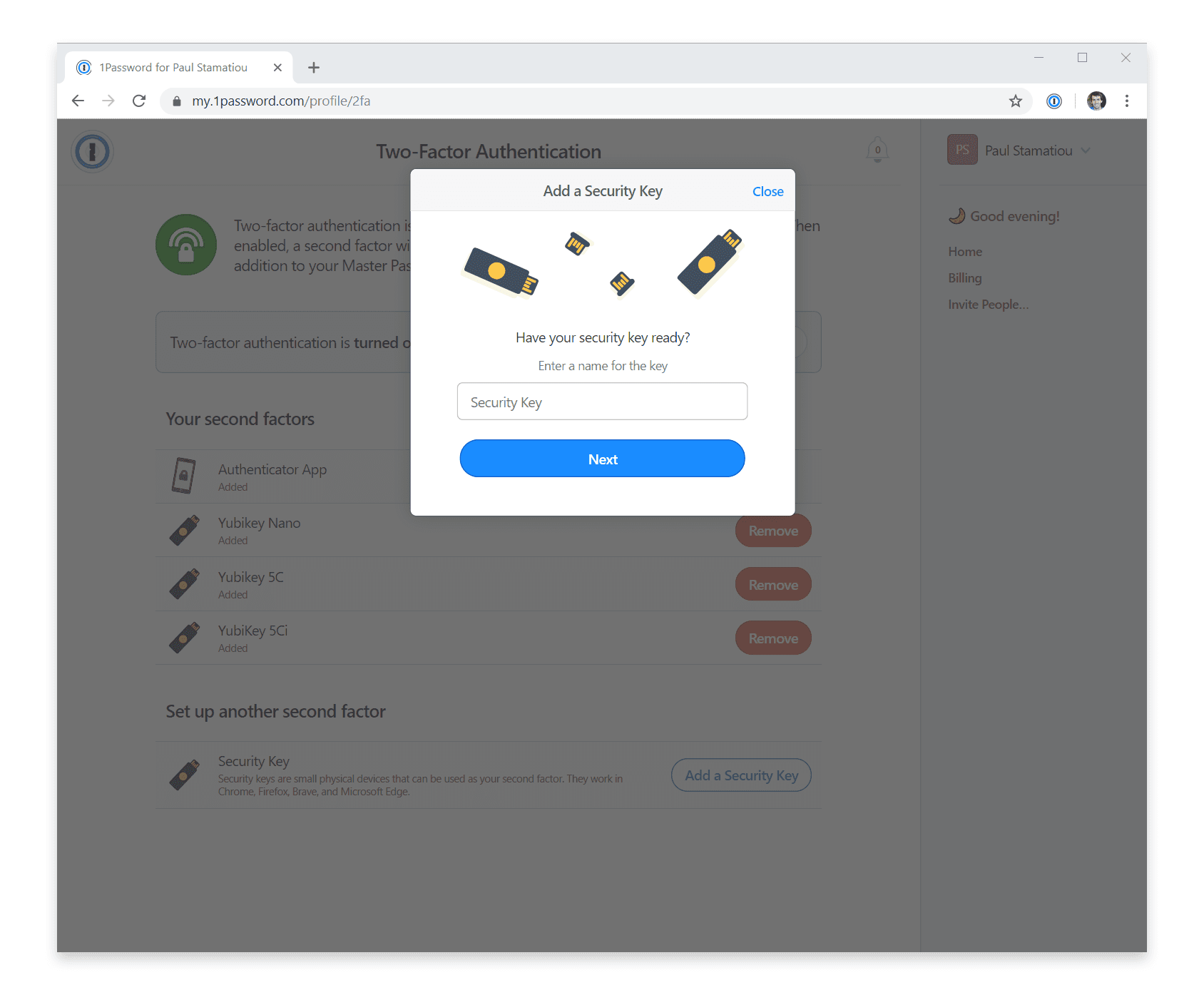

So you've purchased a security key or a few and are ready to set things up.. great! Each security key you own must be registered with each service you wish to use it on such as Google, 1Password, Facebook, GitHub, et cetera.

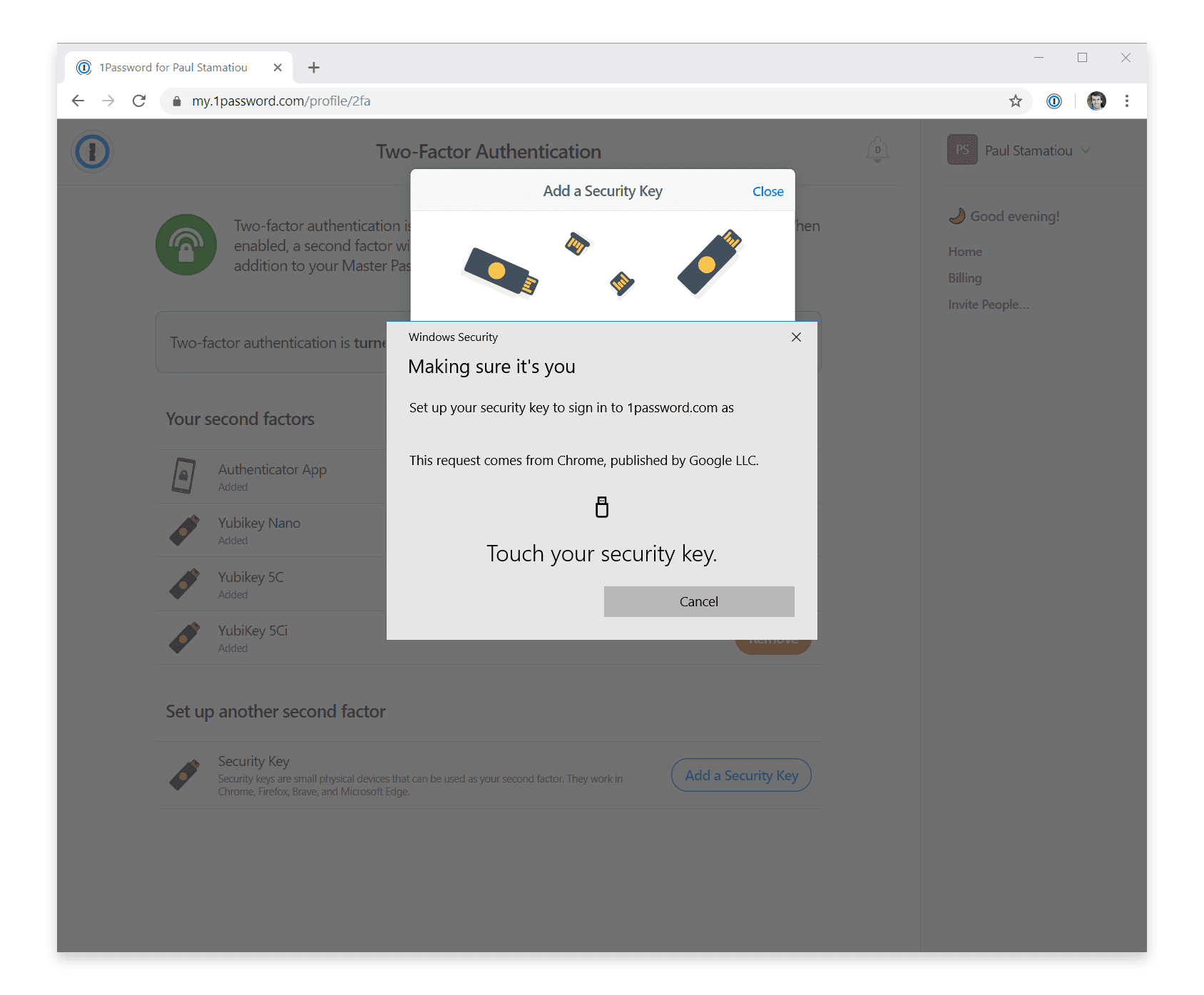

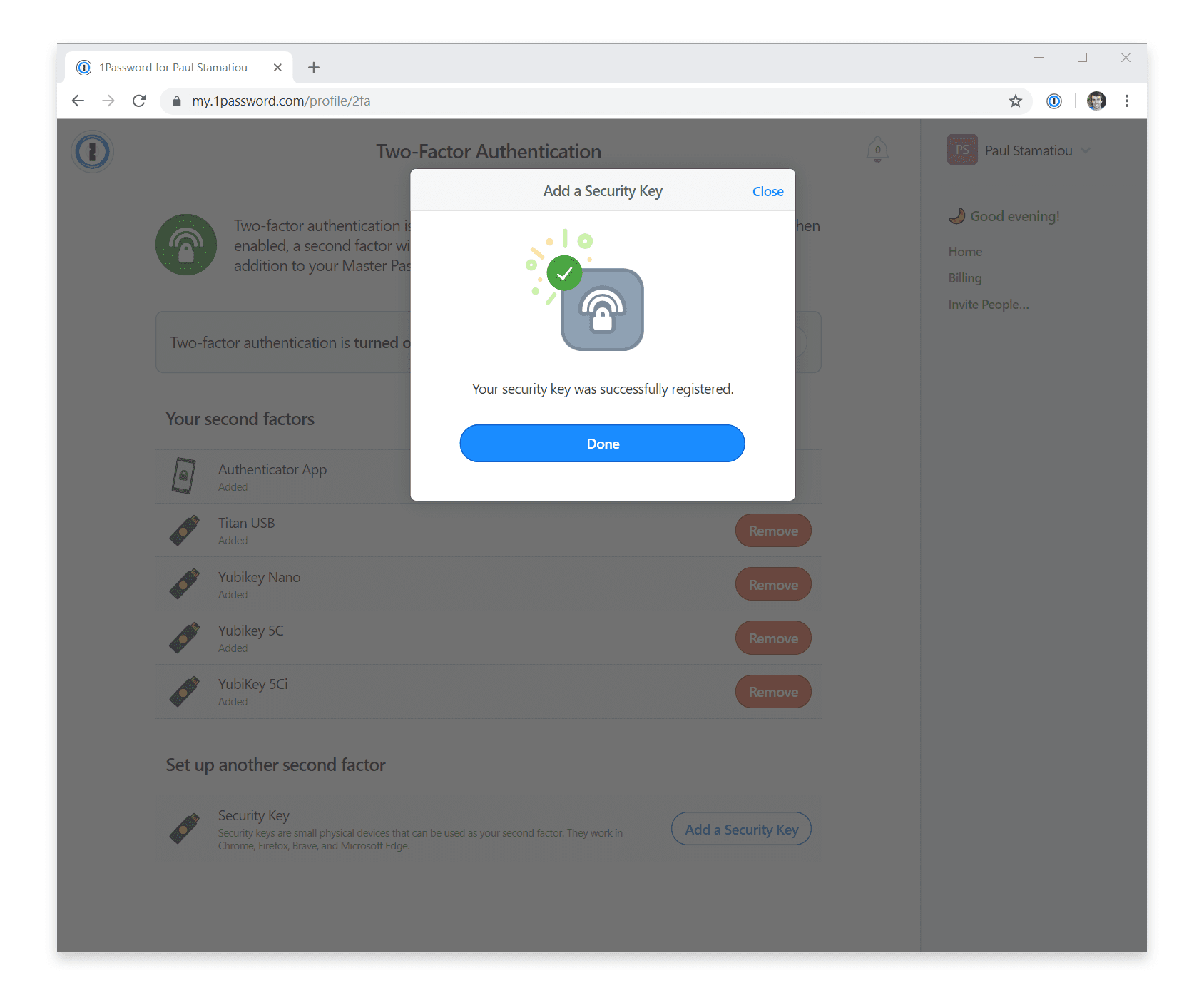

You'll register each key one by one. Usually navigating to the website's settings page related to two-factor auth and finding a button to add a key. This assumes you've already setup two-factor auth. Then when prompted you plug your key in and tap it. Depending on the website you may be prompted to type in a name for each key. This step is vital as it helps you identify which key to remove from the service in the event you lose that key and have multiple registered on the same service.22

And that's pretty much it. Once a key is registered with a service, the next time you log in 23 it's as easy as touching your security key when prompted after entering your username and password.

That's generally how two-factor authentication with security keys works but these things differ from website to website depending on how they've implemented things. For example, you may be prompted for a code from an authenticator app instead (if you have one added as a second factor option) and are in a browser that does not support FIDO U2F or FIDO2 WebAuthn.

YubiKey 5Ci plugged into a MacBook Pro

You can check to see if the websites and services you use support security keys by taking a look at DongleAuth.info. It's also easy enough to search the settings pages of the websites you use for any mention of security keys for two-factor authentication.24

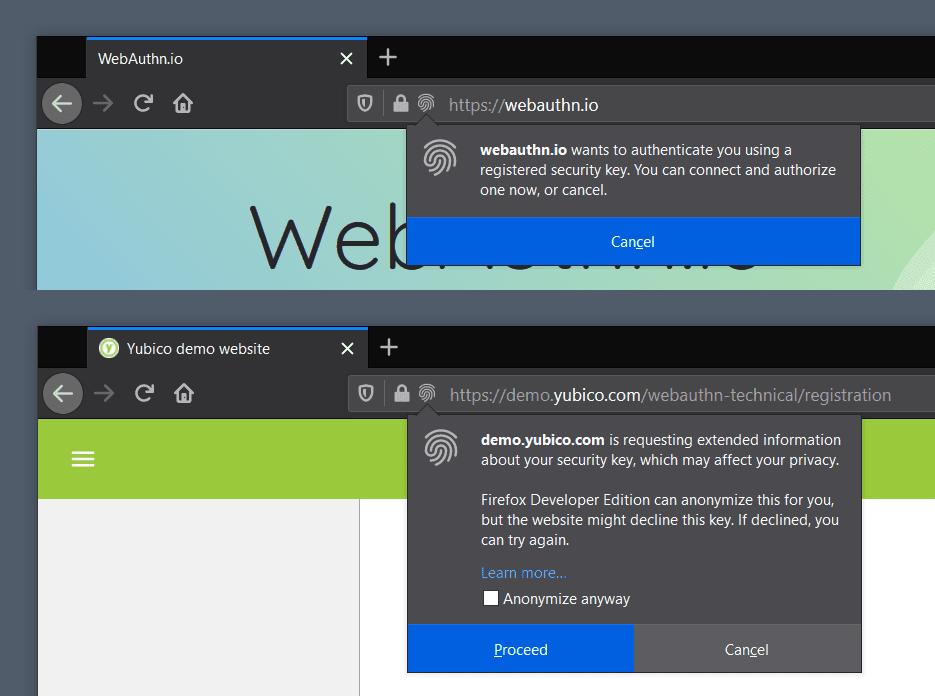

Different browsers will display varying prompts requesting you to touch your security key. Left: Windows 10 Firefox Right: Chrome for macOS Not pictured: Safari 13 for macOS Catalina (while it has experimental WebAuthn support, it shows no UI to prompt for a key yet)

Setting up Google Advanced Protection

Google's strongest, security key-required security program

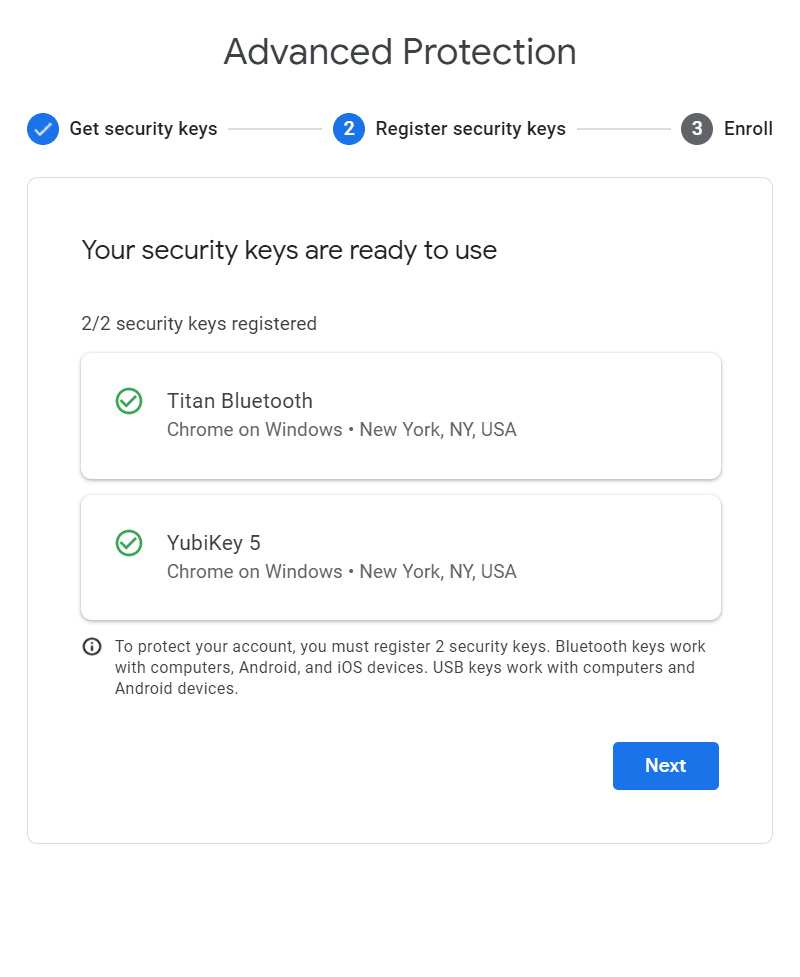

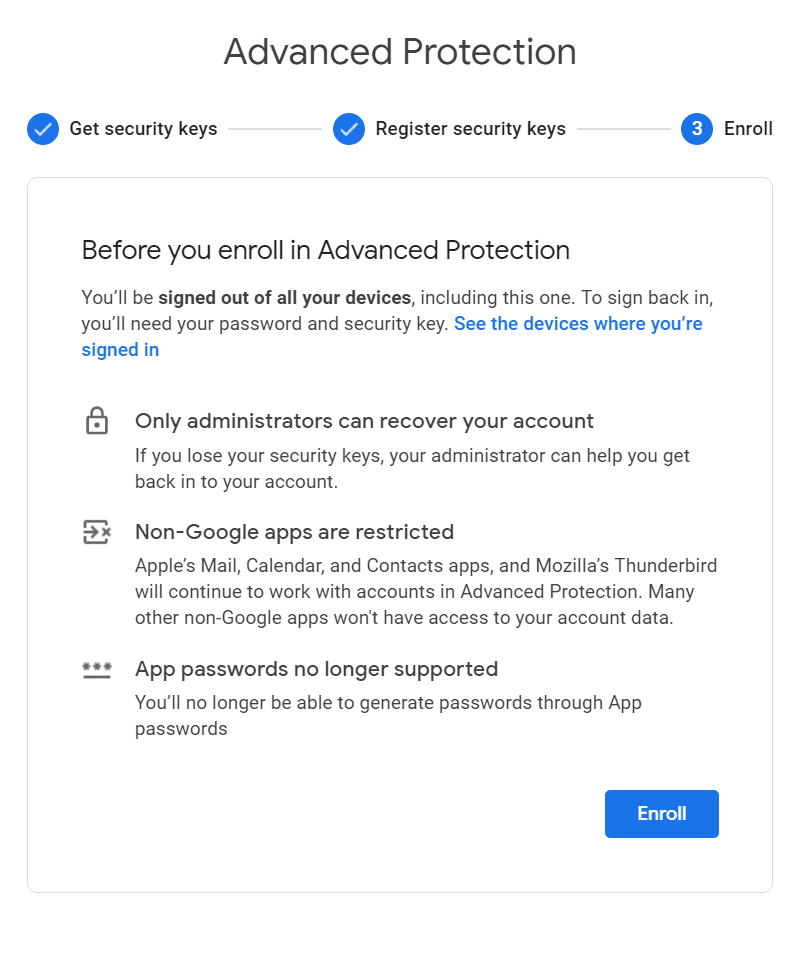

I mentioned the benefits of Google Advanced Protection earlier in this article. It is designed to help thwart targeted attacks by requiring the use of security keys, in addition to numerous enhanced security measures.

Signing up for Advanced Protection follows the same process I mentioned above: enable two-factor auth, register and name two security keys and you're ready to go.

Chrome will ask to see detailed info about your key during the key registration process.

Advanced Protection has some aggressive requirements: you must register at least two security keys, you can't add any TOTP authenticator apps as a second factor and there's no recovery code. You can however add an approved Android device as an authenticator. Google requires having two keys with Advanced Protection so that one can operate as a spare should you lose one.

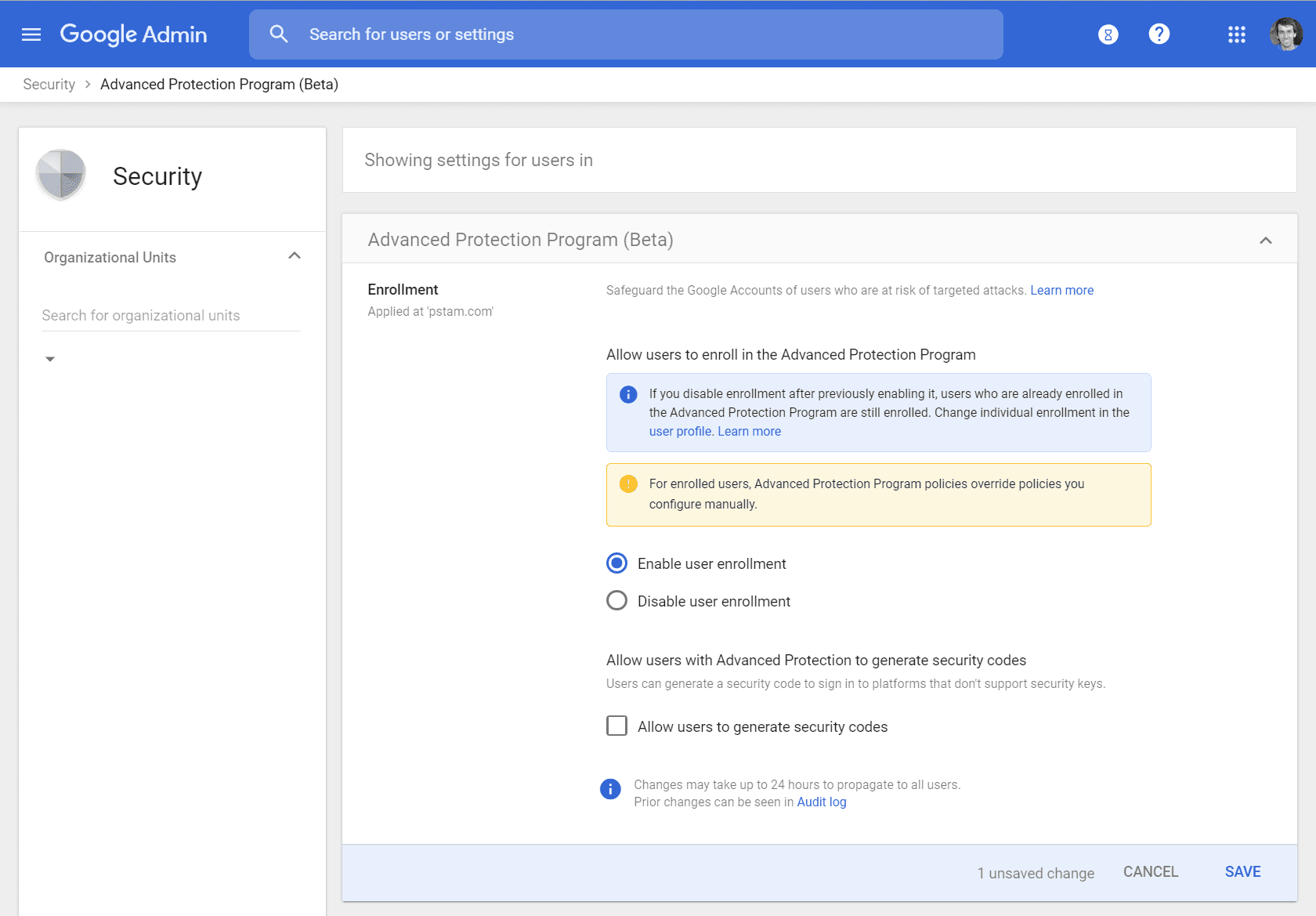

Use G Suite? You'll have to enable it first.

If you use the enterprise G Suite for your email, you may not have the option to even enable the Advanced Protection Program until your administrator has turned it on. If you run G Suite for yourself, you can read about enabling the beta here.

What about regular Google accounts?

If you're not ready to make the jump to Advanced Protection

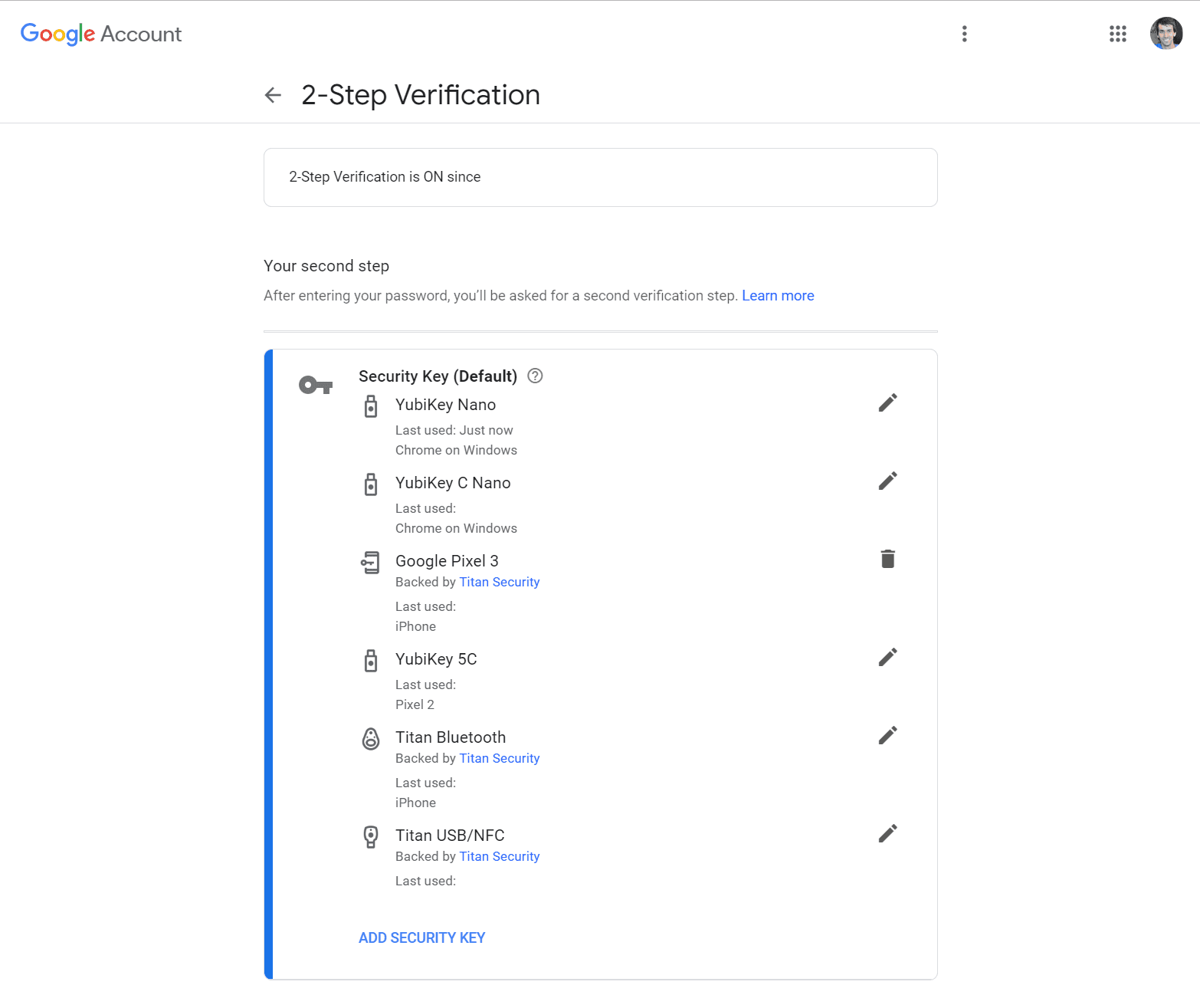

If you just want to test the waters a bit with security keys and don't think enabling Advanced Protection is for you at this time, you can always just register keys as part of any Google account's regular 2-Step Verification settings.

The process for adding a key is similar to the Advanced Protection flow from above but you just navigate to Google Account → Security → 2-Step Verification → Add Security Key.

With regular Google accounts, you're free to mix second factor authentication types from SMS to authenticator apps and even other phones using Google 2SV phone prompts. Of course, I strongly advise against using SMS at all.

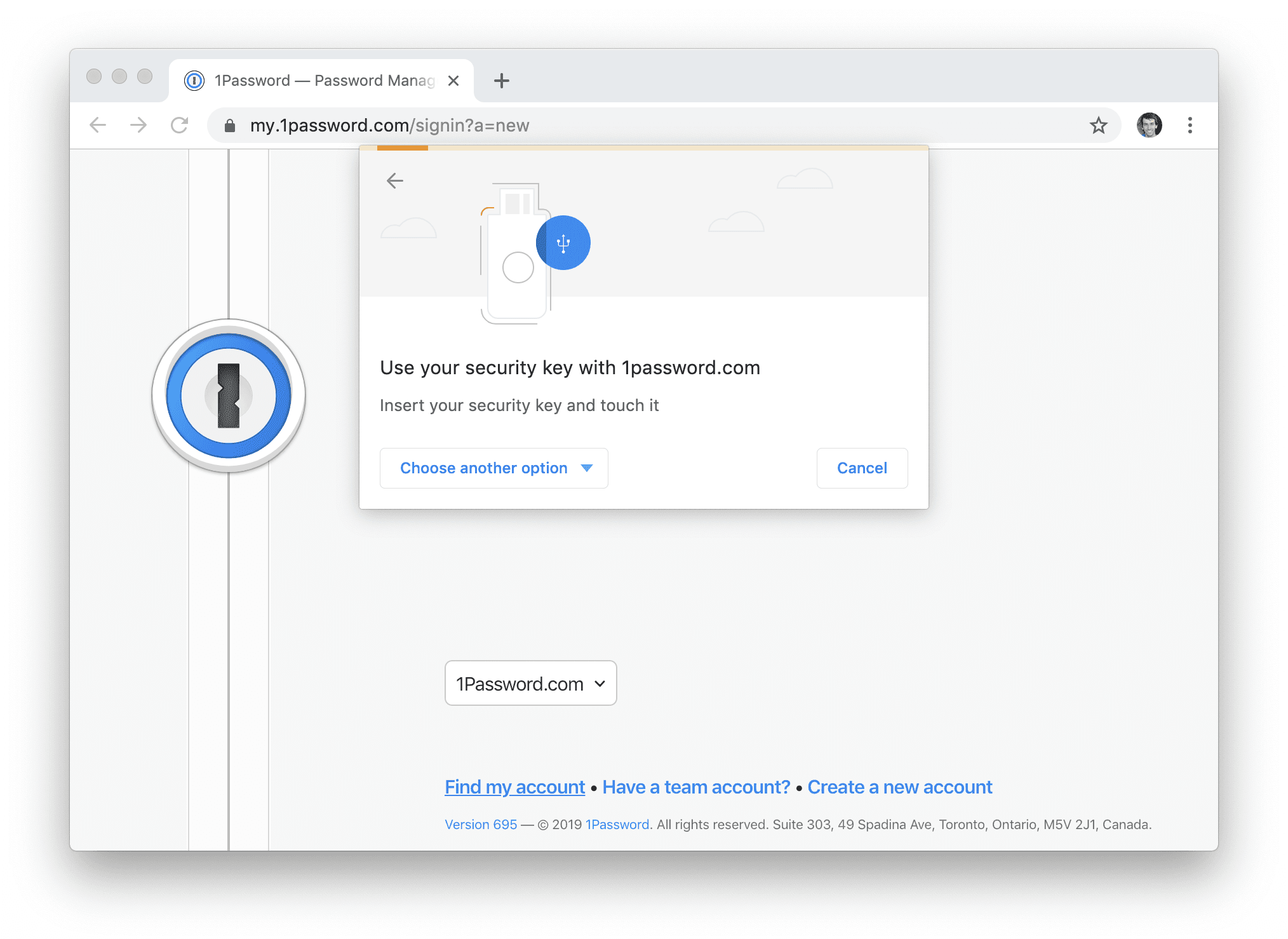

1Password

If you use the hosted option for 1Password password manager, adding your keys is a simple process as well. Just log into 1Password.com, click your name in the corner then navigate to My Profile → More Actions → Manage Two-Factor Authentication → Add a Security Key.

You can add as many keys as you like. However, the current 1Password implementation does not yet allow you to remove the authenticator app as a second factor. Since people often use 1Password on their mobile devices in addition to their desktop computers, they would likely only support security key-only authentication once every 1Password mobile app offered security key support.

Only the 1Password iOS app supports physical security keys at this time and via a custom Yubico Mobile SDK integration only supporting the new and expensive Lightning connector YubiKey 5Ci.. so definitely not for everyone just yet.

Update (May 2020): 1Password for iOS now supports NFC security keys, though only the YubiKey 5 NFC for now it seems.

Will 1Password ask for my security key every time?

Adding a security key does not mean that 1Password will ask for it every single time you need to open 1Password to log into an account: something that likely happen many times throughout the day for you. 1Password only really asks for your security key when adding your 1Password account to an untrusted device like a new browser or desktop app.

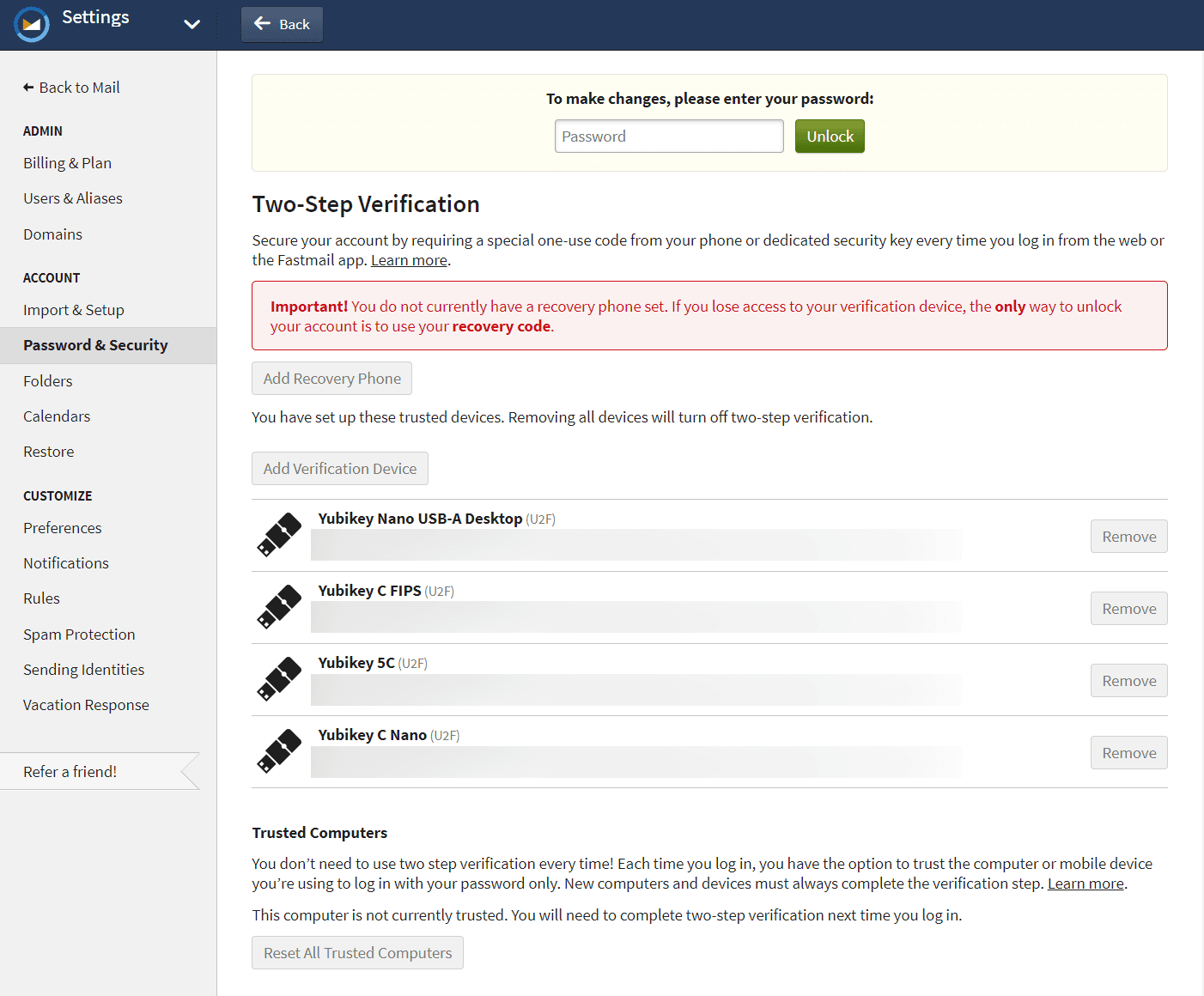

Fastmail

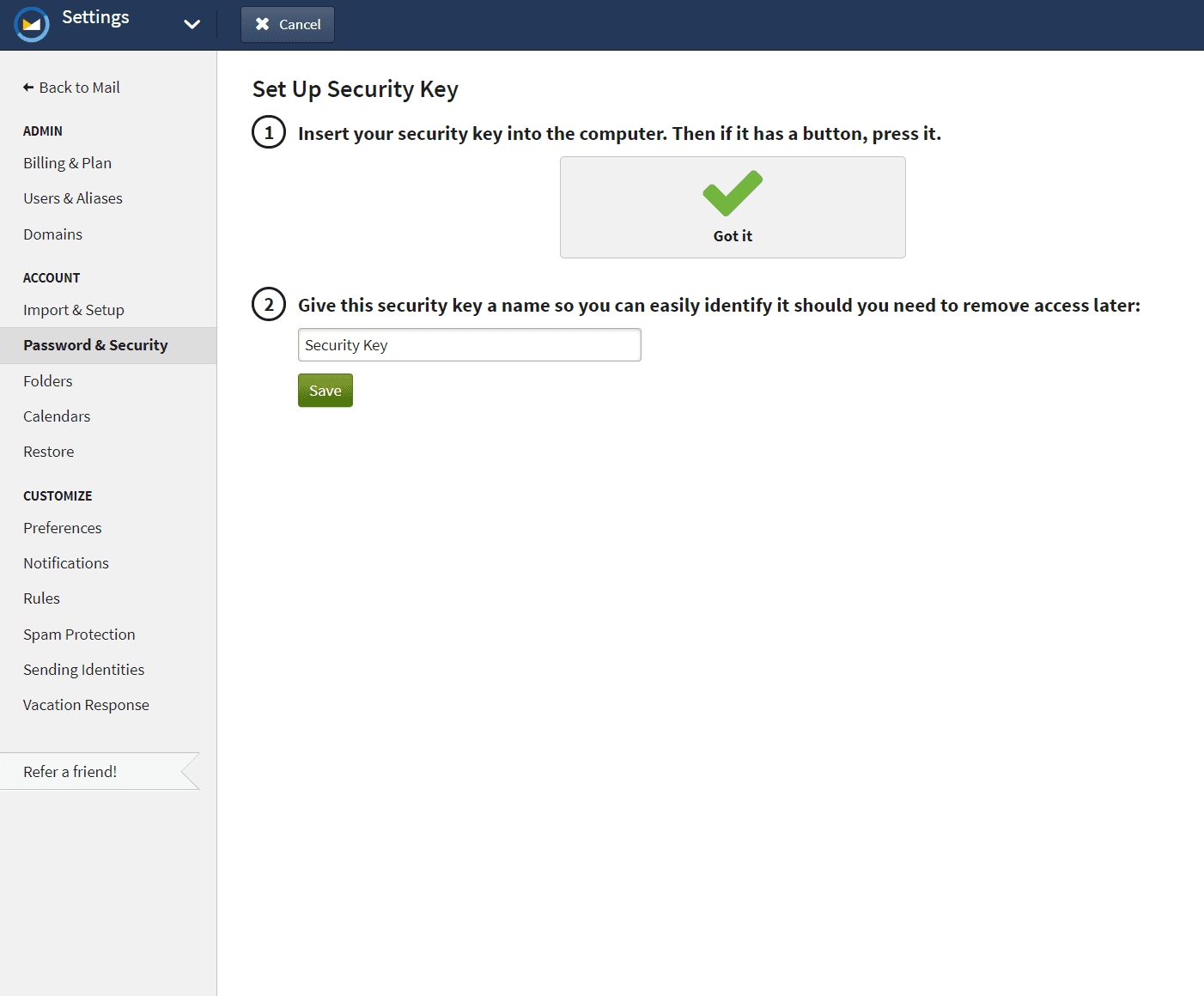

Fastmail is a popular non-Google email service that has supported security keys for years now. It also lets you entirely remove SMS, recovery codes and authenticator apps if you so wish. Setup is trivial as well: Settings → Password & Security → Two-Step Verification → Add Verification Device → Set Up Security Key.

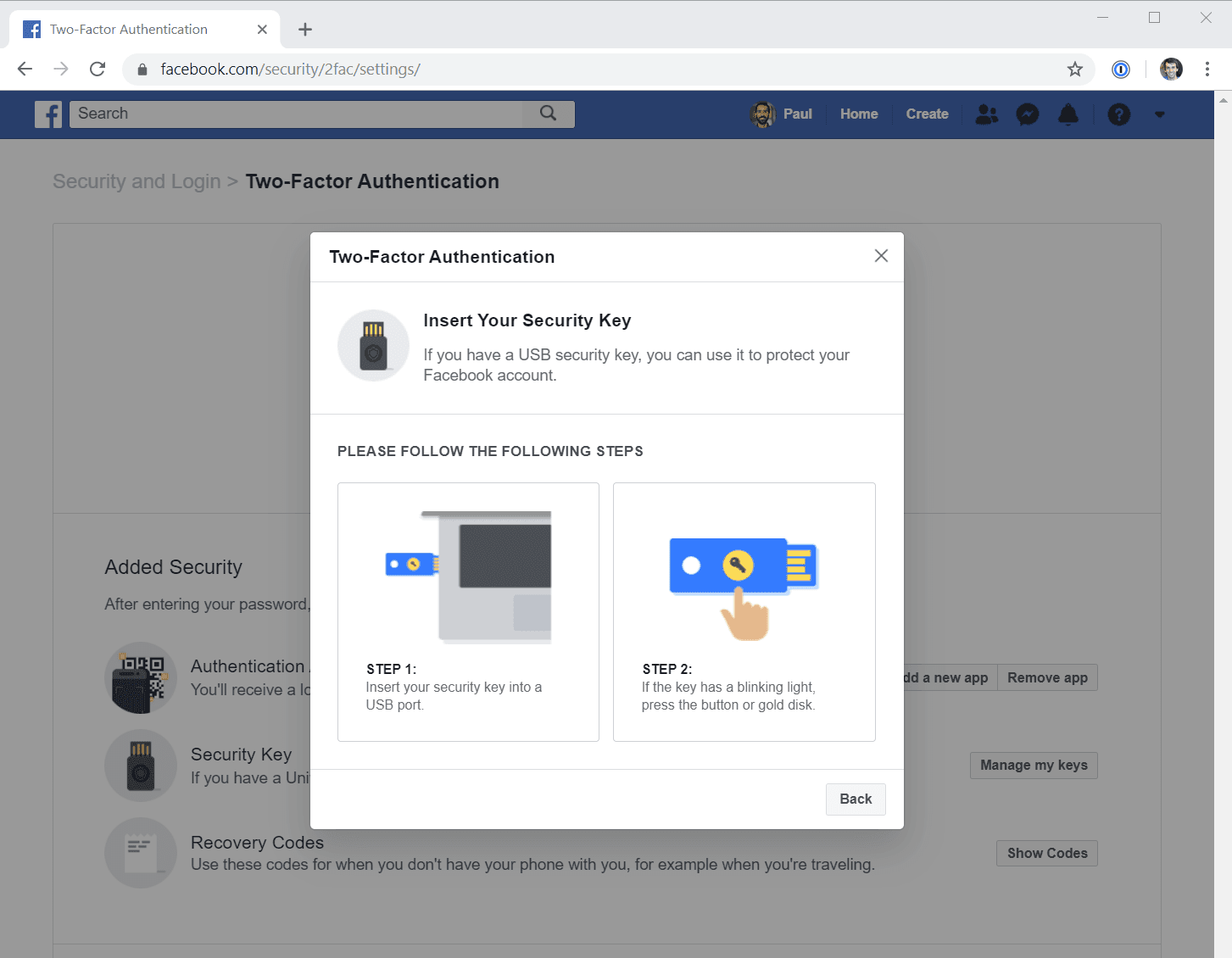

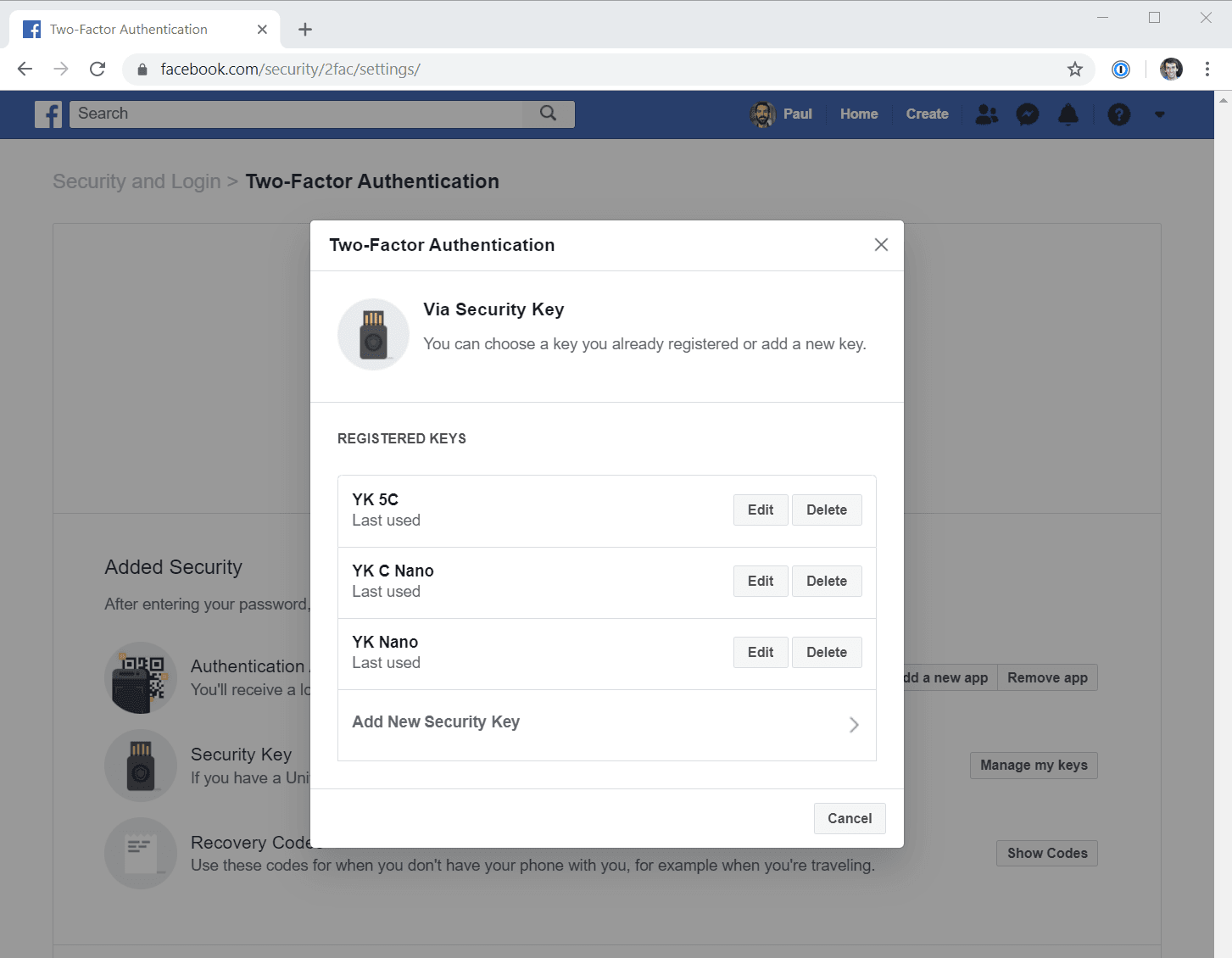

Of course, you can register your security keys with your social accounts like Facebook as well. The process is the same: find the two-factor auth section in the account settings then add and name each of your security keys.

Registering keys on other services

If you have any questions about how to set up your security keys on other services, Yubico maintains a well-documented section on their site for just about every supported service.

What about mobile?

It's easy on Android, less so on iOS..

By now you've registered your security keys and figured out how to log back in with them on your desktop browser. But how do you login on your mobile devices with security keys?

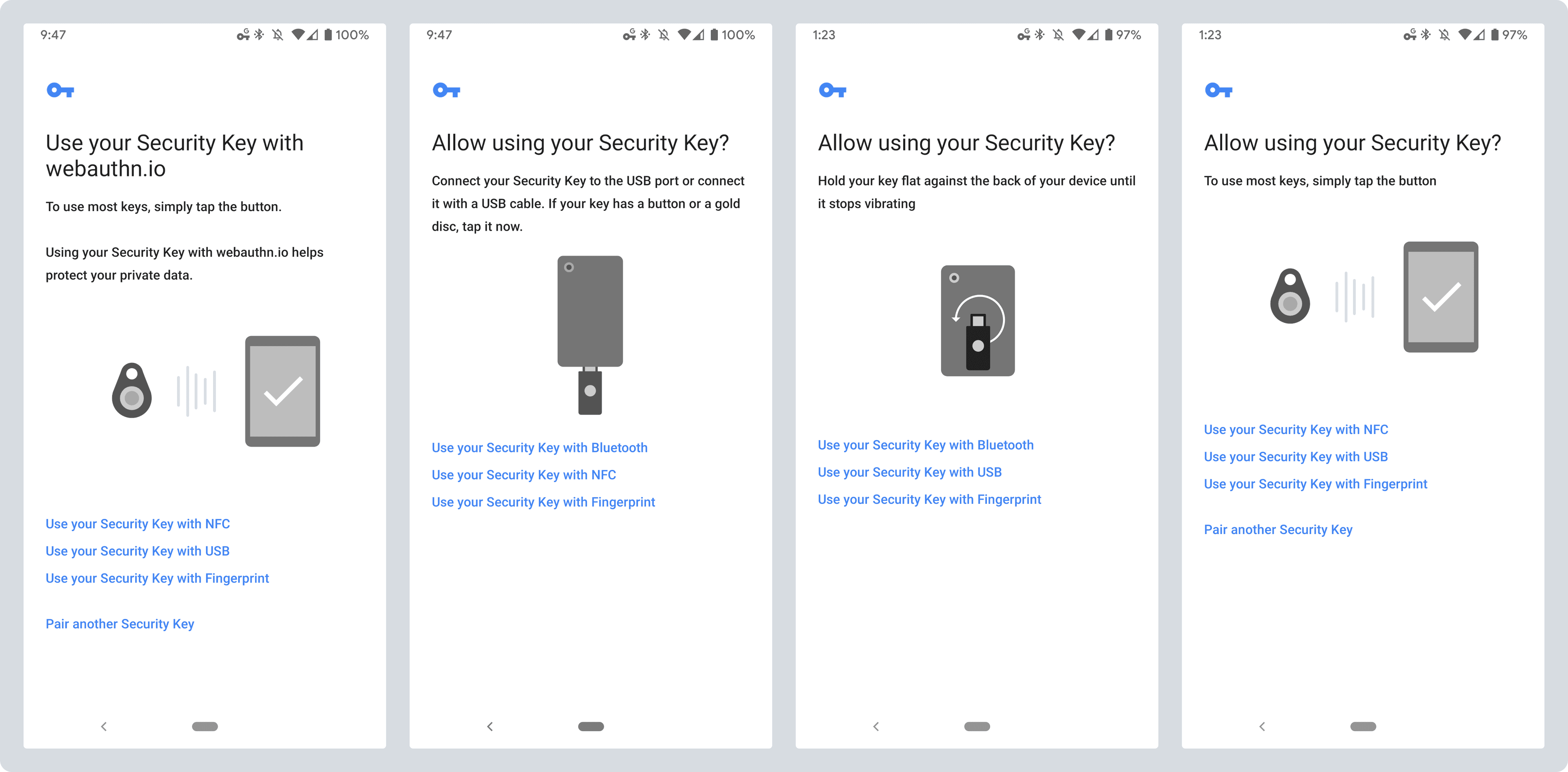

As I mentioned in the Android section earlier, it's a breeze. The operating system itself (well, Google Play Services technically) supports FIDO2 so any website or app should trigger this authentication activity view, giving you numerous authentication options such as with NFC, USB and Bluetooth keys.

Using your security key on Android just works. (Pictured: Pixel 3 + YubiKey 5C USB-C key)

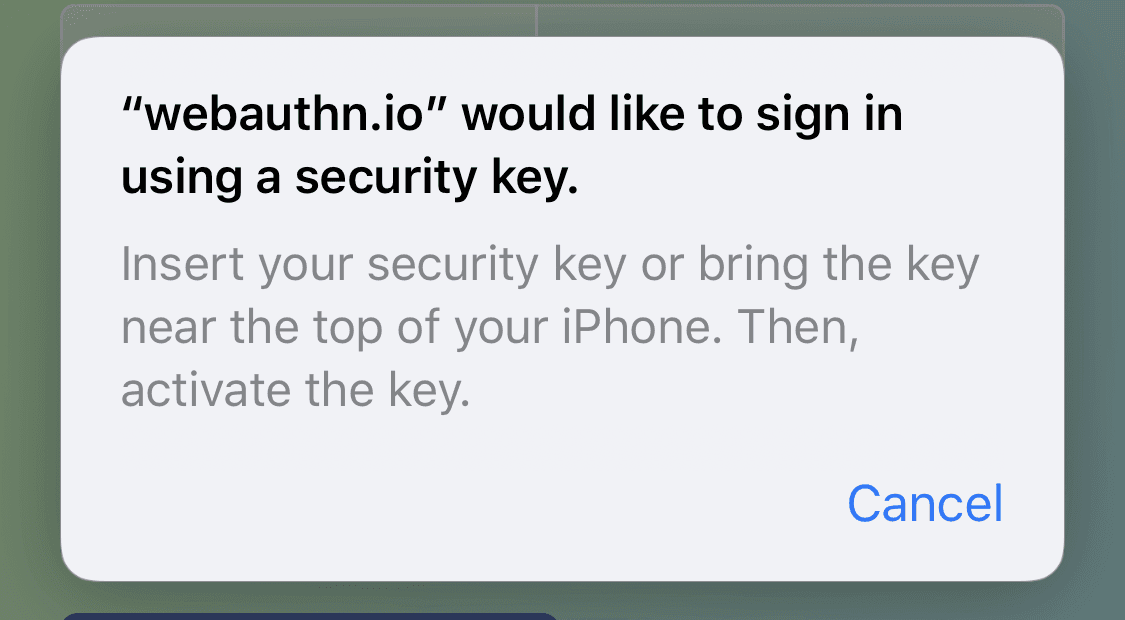

It's not the same with iOS. You're out of luck if your main browser is Chrome for iOS as it does not have support yet. While iOS 13.3 brought support for USB, NFC and Lightning keys to Safari, not all apps and services have taken note yet.

If you use a Google account on your iPhone or iPad, however, you do have another option. Google has a separate authentication app called Google Smart Lock for this purpose. You log into all of your Google accounts in the Smart Lock app—it supports Bluetooth security keys—and it can redirect you back to the app you came from to complete your authentication. This works for native Google apps as well as apps utilizing Google login.

Using a Bluetooth security key on iOS with Google Smart Lock.

It's not a perfect solution but you don't have much of a choice for Google apps and services on iOS right now. Even attempting to log into Gmail in Safari does not let you use a security key directly in Safari; instead it tries to redirect you to Google Smart Lock.

Having to install a separate app just to use your security key is a hassle. Then you add on to that some general Bluetooth security key woes: having to pair the key, having to keep your security key charged at all times, having to carry around a MicroUSB cable around to keep the key charged, having the key's button always accidentally get pressed in your bag and drain the battery. Annoying.

However, I'm hoping that in the first few months of 2020 we'll begin to see more apps and services update to support security keys, at least via utilizing SFSafariViewController to take advantage of the existing WebAuthn implementation.

Bonus: Pixel 3 as a security key

Take advantage of the integrated Titan M security chip

This probably isn't what you have in mind right now when you think about a security key. For most of this article I've been talking about external hardware authenticators that you plug into your computer or mobile device. But they don't always have to be separate from your device.

More and more devices have integrated security chips, some Google Chromebooks even have an integrated "H1" chip that can be used for FIDO U2F auth. These integrated security chips may go by various names like secure element, TPM and Apple's Secure Enclave, but the gist is generally the same. They are secure cryptoprocessors that have a secure boot process and microkernel to completely isolate itself from the rest of the hardware. Much like USB security keys, the system cannot access the secrets stored on the security chip: the chip itself just runs computations. Now, with WebAuthn and initiatives like this Google solution I'm about to describe, there are more ways for these chips to be used for web authentication.

But I digress... the Pixel 3 has a "Titan M" security chip that can be used to store your cryptographic keys for second factor authentication. This is similar to how an external security key is used to generate a unique public/private key pair for auth. When you go to Google account settings to add another second factor for 2-Step Verification, it will display a prompt to add your Android device if it recognizes that your Google account is logged in and supported. While it supports any Android device running Android 7+, it's only the Pixel 3 (and I'm guessing the new Pixel 4 can do the same) that features this enhanced protection. (Update January 2020: Google has updated the Smart Lock app for iOS to enable similar functionality for iOS users.)

Adding the Pixel 3 as a second factor to a Google account.

It's important to note that this is not the same type of phone prompt you may have seen in the past where your phone receives a login request notification via the cloud. This new implementation is quite novel: it's local proximity based, and as such it requires Bluetooth to be enabled on both devices. Also, Google was able to get this working entirely without requiring Bluetooth pairing, which is always a hassle. They developed an extension to WebAuthn that introduces pairing-less secure communication between your computer and the mobile device.

When you log into your Google account, it will communicate with your phone locally via Bluetooth. Similar to an external security key, user presence is required in the form of a physical press. Google had the security chip hardwired to the Pixel 3's volume down button. As such, not even malicious software running on the phone would be able to control the Titan M chip on its own.

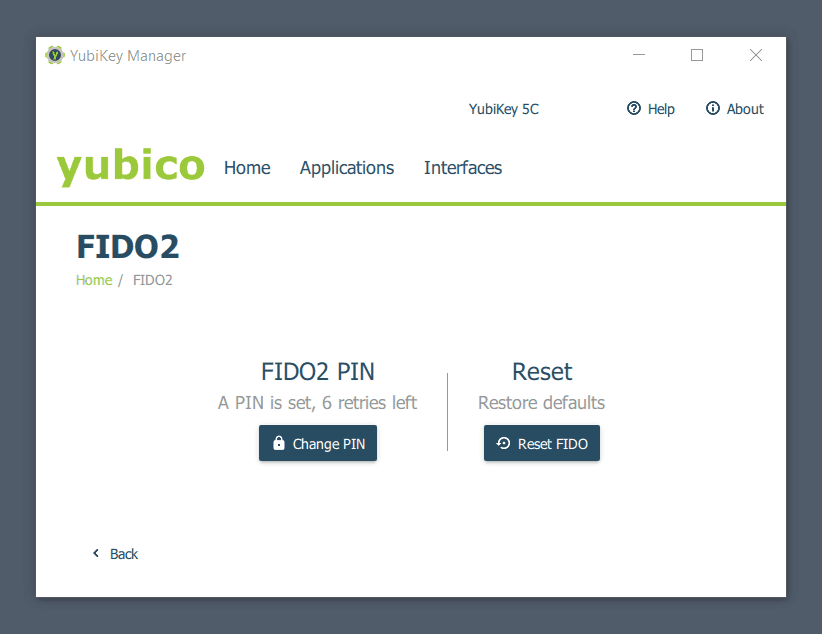

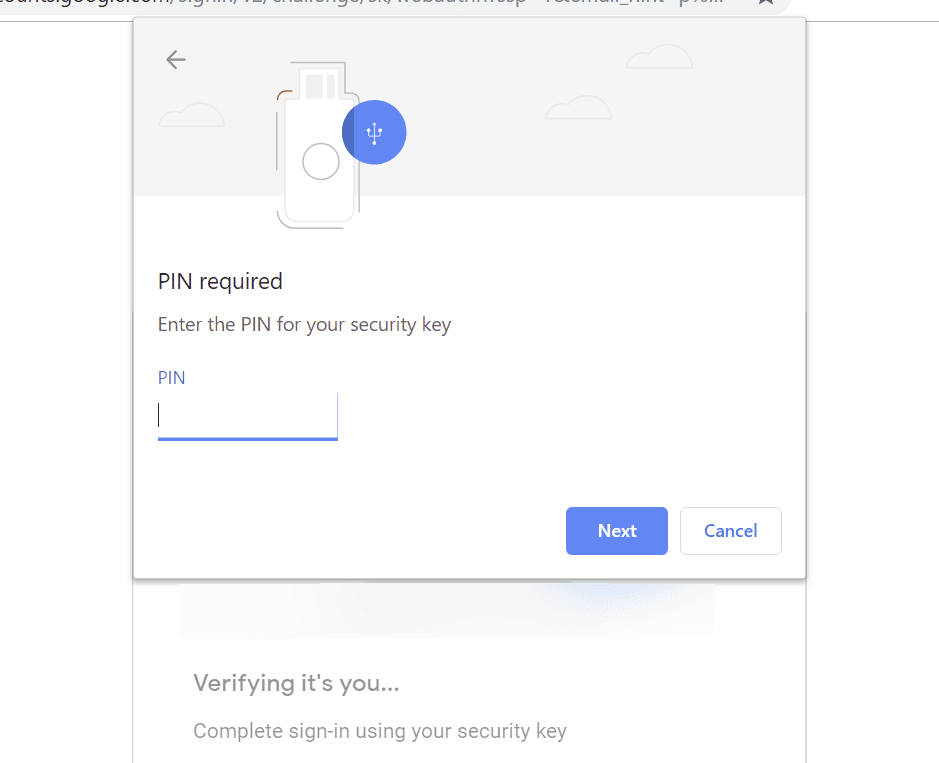

Why does it ask for a PIN?

Set a PIN to enhance user verification on your FIDO2 key

If you're using a FIDO2 security key you may have been prompted at some point during the registration process or elsewhere to set or enter a PIN for the key. This was confusing to me the first time it happened, especially when I was using my key as a second factor.

Of course, there is a reason for this. But first, I'll go ahead and say that for the purpose of using the key as a second factor only, you don't need to set a PIN.

Left: Setting a FIDO2 key PIN in YubiKey Manager Right: Chrome for macOS prompting for the PIN.

The PIN is there to enable a form of multi-factor authentication for passwordless authentication flows. We're not quite there yet as not many services support passwordless functionality, but the modern security keys support it. FIDO2 keys have the ability to store username and password credentials directly on the key, via FIDO2 resident credentials.

This is a significant change to how things were done with FIDO U2F where it was not possible to know which services had been registered with the key. Now with resident credentials it's possible for someone to ask the key to list out what domains it has been registered on or just what accounts exist on the key for a given domain. As such, you need a way to add a stronger user verification step to limit that access. In this passwordless world, your FIDO2 hardware key can require user verification with a PIN that is local and stored directly on the key itself, or it can require something like a biometric gesture if the device has such sensors/readers and was configured that way.25

But wait, I thought this was supposed to be passwordless.. why do I need to set and remember a PIN? Yubico has the reasoning here:

A PIN is actually different than a password. The purpose of the PIN is to unlock the Security Key so it can perform its role. A PIN is stored locally on the device, and is never sent across the network. In contrast, a password is sent across a network to the service for validation, and that can be phished. In addition, since the PIN is not part of the security context for remotely authenticating the user, the PIN does not need the same security requirements as passwords that are sent across the network for verification. This means that a PIN can be much simpler, shorter and does not need to change often, which reduces concerns and IT support loads for reset and recovery. Therefore, the hardware authenticator with a PIN provides a passwordless, phishing-resistant solution for authentication.

Final words of advice

Keeping track of your keys

If you're like me you probably have quite a few websites you will be using your security keys with. If you have more than a few security keys it may be handy to make a spreadsheet of each key you own and each service it is registered on (or in your password manager, add a note for each login about what keys are registered with each service.

Done. Now I’ll just have to wait for banking hours when I lose my other u2f keys and lock myself out of my accounts 😂 pic.twitter.com/kC2NmX8TTa

— Paul Stamatiou 📷 (@Stammy) August 15, 2018

This is particularly handy if you store any of your keys at separate locations for safekeeping and need to know which ones to register on new services when you get a hold of them next.

Which brings me to my next point, if you have more than one security key, you should keep the spare somewhere safe. That could be a trusted friend or family member's house, it could be your place of work, a bank safe deposit box, et cetera. Unless you think you could be targeted, this is likely just to prevent you from misplacing the spare security keys at your place.

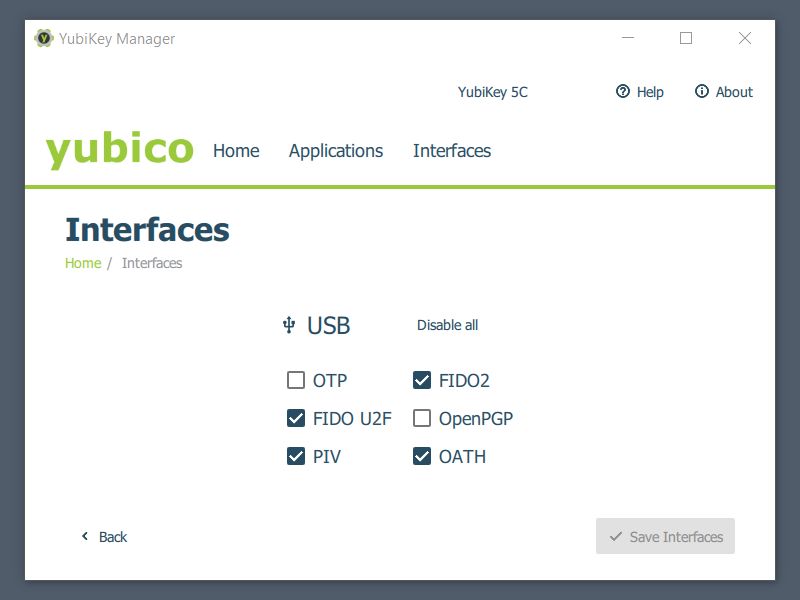

Pro tip: Disable Yubico OTP mode

There's one common annoyance with the default YubiKey configuration: accidentally tapping the button on a YubiKey will make it begin spewing out a large string of random characters each time. Contrary to popular belief, this is not related to actual FIDO/FIDO2 functionality. It's a mode specific to YubiKeys for another type of authentication that you probably won't be using: Yubico OTP.

This is distinct from the TOTP you already know about for generating app codes, and different from using your YubiKey to store TOTP secrets. Here's more detail about Yubico OTP.26

The point here is that having a long string accidentally get inputted into whatever application or document you were working on will drive you crazy. It happened to me one time when I was working in Adobe Lightroom as I reached over to plug in a USB SD card reader and accidentally tapped the YubiKey in the other USB port.. and let me tell you, Lightroom went crazy and interpreted every keystroke as a command. It took me a while to undo that mayhem.

Needless to say, I disable Yubico OTP mode on every YubiKey I own. Fortunately, it's very easy. Install the YubiKey Manager app and uncheck OTP mode:

On the Interfaces tab uncheck OTP and save.

FAQ

Because this is entirely more complex than it should be

What is a security key?

Security keys, security tokens, U2F keys, roaming authenticators, platform authenticators—whatever you want to call them—are hardware authenticators that run public-key cryptography operations in a manner that is entirely isolated from the rest of mobile device or computer. There are two general classes of security keys: internal platform authenticators and external roaming authenticators.

Platform authenticators are integrated inside of a device. They may take the form of an integrated security chip accessible by software for the purpose of web authentication, such as the security chip in the Pixel 3, or biometrics devices like fingerprint readers and facial recognition sensors.

This article has primarily been about other variant: roaming authenticators. These are the little external hardware authenticators you connect to any device (via Bluetooth LE, NFC or USB) to carry out your authentication needs. They communicate with your computer via FIDO CTAP (Client to Authenticator Protocol).

In one sentence, why is a security key better than an authenticator app for two-factor authentication?

There are several reasons (view the keys vs TOTP section above), but the main one is that security keys prevent phishing by using public-key cryptography that verifies the domain you're attempting to authenticate with is the same one you originally registered your key with.

What services and browsers support WebAuthn?

See the compatibility section above. For the most part, support is great across Windows, Linux, ChromeOS, macOS and Android. iOS is getting there with recent Safari support for USB, NFC and Lightning connector security keys. However, many iOS apps and browsers still need to catch up.

As for what websites support FIDO2 WebAuthn (and the earlier FIDO U2F) for two-factor auth, it's probably easiest to just log into the website and poke around the security and two-factor auth sections. You can also check DongleAuth.info or the Yubico catalog. FIDO2 WebAuthn also supports passwordless functionality but the vast majority of websites do not support that at this time.

How often do I need use my security key?

This depends on the exact implementation for each website, but for the most part: not that often. Most services only prompt for your security key if you are using an untrusted browser or device. For example, after logging in the service will mark your browser as trusted for 30 days, or until you log out. However, if the service thinks something is weird like you are logging in from a different IP in another country or you're in a new browser, you will need to do the full two-factor auth login with the security key.

For mobile apps like Gmail, it seems to not automatically expire the trusted client status. You only need to present the security key the first time you add your Google account to the phone.

Whether this means you should carry around your security key with you at all times is up to you. But if you're traveling, I would definitely take it. And a second key as a backup (assuming you still have a spare somewhere else safe) that you store in a different place while traveling. This is similar to how I travel with SD cards when on photography trips. I keep a set of SD cards on me and a duplicate set of SD cards (or imported to my computer if traveling with one) at my lodging, until I'm able to get home and load it on my NAS.

What happens if I lose my security key?

You just log in with your spare security key and remove the security key you lost from the account. Easy.